Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Icon and Mirror

-

Dirty Work

-

Oh, to Weld!

-

Insights on Work

-

Carl Sandburg’s “Buffalo Dusk”

-

To-Do List

-

Mercenaries out of the Gate

-

Loneliness at College

-

An Economy for Anything

-

The Artist of Memory

-

Poetry and Prophecy, Dust and Ashes

-

Valor

-

Editors Picks Issue 22

-

Carl Sandburg

-

A Difficult Love

-

Covering the Cover: Vocation

-

The Noonday Demon

-

Captivated by the First Church

-

Sometimes I Wince at the Weight of your Hand

-

Why We Work

-

Readers Respond: Issue 22

-

Buccaneer School

-

The Unchosen Calling

-

A Life beyond Self

-

Insights on Vocation

-

Monks and Martyrs

-

A Love Stronger than Fear

-

Now and at the Hour

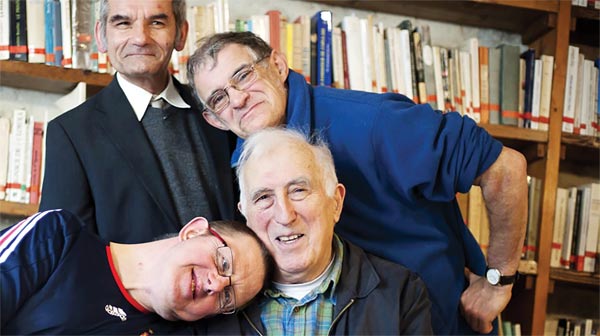

Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche community movement, died on May 7, 2019, at age ninety. In this excerpt from a new biography, Vanier finds that the core members of his community, those with severe physical and intellectual disabilities, still have much to teach him about himself.

Editor’s Note: Several months after Plough published this book and excerpt, an investigation revealed that Jean Vanier had sexually abused at least six women. Plough has taken the biography out of print.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

In 1980, Jean Vanier decided to resign from his position as director of the L’Arche community in Trosly in northern France and take a year’s sabbatical. The following year, in November, he moved to La Forestière, a L’Arche house for people with severe disabilities that had opened in 1978. This had been a dream of his for a long time.

La Forestière, surrounded by the forest, as its name suggests, was a new, one-story building constructed around a bright central patio. It was flooded with light from the large bay windows that opened onto the garden. There was a fireplace in the large room where one could stop for a cup of coffee or for evening prayers. It had a small chapel with a very low altar that allowed a person with disabilities, stretched out on the knees of an assistant seated on the ground, to see what was happening. The atmosphere was peaceful. People here took their time; the community seemed to move in slow motion. This was a place where there was plenty of time to get close to one another, so that someone who is blind and deaf could touch a person who approaches. There was plenty of time to bathe Eric – a resident whose body was curled up by disability and despair – slowly unknotting his limbs, letting him feel the warm water, letting him play with the soap, washing him. There was plenty of time to feed Lucien, so that he might feel the pleasure of tasting, swallowing, and smelling the food. These broken bodies were touched with respect and tenderness. While someone gently wiped away the saliva dripping down Henriette’s chin, someone else gently took hold of the hand of Loïc, who had just struck himself violently on the nose. They restrained him without harshness, respecting what he might have been trying to express by his actions, reassuring him that he had been heard, and he was not alone.

At La Forestière one must learn to understand the language of the body. It is a language of tenderness and frailty. The body, which is exalted in athletics and fashion and despised in sickness, aging, and disability – this same body is, the apostle Paul writes, a temple of the Holy Spirit. The broken body, then, is a broken temple that lets the light of God pass through more easily. Jean Vanier knows that the Gospel is the story of a God who chose to be born in human form, with all its brokenness and frailty:

The Word did not become flesh

in the same way one puts on a piece of clothing

only to discard it again;

it is flesh becoming divine,

becoming the means by which that life of love

from God

in God

communicates itself.

That life is not an idea that can be learned

from books or teachers;

it is the presence of one person to another,

the total giving of oneself to another,

heart to heart,

in a communion

of love.

As Francis of Assisi’s encounter with lepers allowed him to discover “a new softness in his body and spirit,” La Forestière was a decisive new step in the life of Jean Vanier. For a year, he experienced the rhythm of life with these men and women with severe disabililties – the rhythm of Eric, for instance, a seventeen-year-old who was blind, deaf, and unable to walk or feed himself. Abandoned in a hospital at four years of age, he was so desperate for human contact that he clung with all the strength in his arms to anyone who passed close to him. Jean discovered that Eric reciprocated all the love he showed him. Jean washed, clothed, fed, and calmed him, reassuring him by these actions that he could be loved, and therefore that he was lovable. For his part, Eric introduced Jean to a new form of peace. Jean writes:

At La Forestière, every evening after dinner, I put Eric in his pajamas, then we spent a half or three-quarters of an hour in prayer, all of us together in the living room, both the disabled people and the assistants. I often sat with Eric on my knees; he rested. And I discovered that I rested with him. I didn’t feel like talking. I was at peace, with an inner quiet. He also was at peace; he also felt content. It was a moment of healing. I found inner harmony again.

But those times when Eric clammed up, howling and writhing, when nothing could calm him down and he was overwhelmed by darkness, Jean Vanier found a door opened to hidden distress, violence, and fear buried in his own heart. He discovered a whole world of chaos and hate within himself that he had carefully masked with his education and intelligence or buried in his work and activities.

Reflecting on such angst is a recurring theme in Jean’s thought. He has realized that it is an inescapable part of the human condition. “Cows do not experience anguish,” he jokes. Contained in a secret part of our being, this anguish can emerge suddenly, along with the violence it produces, at the least hurt. Jean says he still feels within himself today that “it is like a bomb ready to explode, driving us to call for help.”

Discovering his own inner violence has allowed him to recognize similarities between himself and the intellectually disabled he cares for, similarities to which he had previously been blind. He feels as though he has been knocked off an invisible pedestal – his goodness – which is humiliating, but also liberating. “I have been brought face to face with my own deep reality, with my own truth… . I begin to be myself. I no longer play the great and powerful grownup, striving for first place, for success, and for admiration; I am no longer worried about appearances. I allow myself to be the child that I am, the child of God.”

At La Forestière, then, it is no longer a question of Jean Vanier and Eric – the adult and the miserable child – but of “two children playing a game of the soul,” a game which, the poet Pierre Emmanuel tells us, connects us to “the fields of eternity” where all springs of love find their superabundant source. Communion – that other word for love – allows us to be together in God, Love Himself, who unites and gathers us. Eric evokes this mystery of peace and union in anyone who comes close to him and takes time with him, because he does not ask for anything more, and does not try to control or dominate or use anyone.

In his relationship with Eric, Jean Vanier was finally able to understand this sentence from the Gospels that he had heard many times: “Whoever welcomes this little child in my name welcomes me; and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me. For it is the one who is least among you all who is the greatest.” (Luke 9:48) Jean reflected in a newsletter, “This is the mystery that is revealed to us in L’Arche today: the poorest person leads us directly to the heart of God. The smallest one heals our wounds, sometimes by painfully revealing them to us. And that healing and that experience of Jesus and his Father come through the heart-to-heart relationship of mutual trust that grows between us.”

Photographs from https://www.jean-vanier.org.

Dr. Anne-Sophie Constant lectured at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris until 2012. She has been a close friend of L'Arche and Jean Vanier for decades.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Bob Taylor

Brings me to tears, the more so when I consider the coldness and hardness of heart of people I am related to.

Gary Demers

Beautiful story,..excellent article. Touched!

Rachael J Wainwright

Thank you so much for this beautiful insightful article. Humbling & truly challenging....blessed indeed to be able to read this...