Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Christ the Physician

-

What’s a Body For?

-

Begotten Not Made

-

The End of Medicine

-

Perfectly Human

-

Let Me Stand

-

All Sorts of Little Things

-

The Measure of a Life Well Lived

-

Siegfried Sassoon’s “Before the Battle”

-

Editor’s Picks Issue 17

-

Our Task Is to Live

-

To Be Plucked by a Strange or Timid Hand

-

The Beguines

-

Carry Me

-

The Soul of Medicine

-

Readers Respond: Issue 17

-

Family and Friends: Issue 17

-

The Hunter

-

Beyond Racial Reconciliation

-

Science and the Soul

-

Money-Free Medicine

-

Patient Perspective

-

On Being Ill

-

On Eternal Health

I am an old-school family physician who has spent the last thirty-eight years tending to the population of Hamilton County in the center of upstate New York’s Adirondack Park. Hamilton County features the lowest population density of any county in the eastern United States, at 2.6 people per square mile. The people are rugged, stoic, and self-reliant. For economic and geographic reasons, providing health care to them is an ongoing challenge.

Devoting my life’s work to practicing rural family medicine in the Adirondacks has been a very rewarding experience. It is true that choosing that path meant placing myself in the lower end of the earnings bracket for my specialty, which is itself one of the least profitable fields in medicine. But my rewards, while less tangible, cannot be bought with money. In the hamlets of North Creek and Indian Lake, I have been able to experience the traditional role of town doctor, where I know almost everyone and almost everyone knows me.

This is especially true when caring for the elderly and infirm who cannot or will not leave their homes. Although they are time-consuming, I dedicate one day every two weeks to doing home visits throughout my practice territory, often driving 100 to 150 miles to visit six to ten patients who are too elderly, frail, or ill to travel. I have discovered that this can be a very spiritual experience, especially when the person’s medical needs no longer include aggressive or hospital-based care. We can focus on maintaining the individual’s comfort, reliving old times, giving reassurance, preserving the patient’s dignity, and making sure all concerns are being addressed. I often feel more like a member of the clergy than the medical profession, and it makes me realize how much the two professions have in common.

Visiting a patient in her last days Photograph by Art Wiser. Used by permission.

I have witnessed the digitalization, hyper-specialization, over-regulation, and dehumanization of medical care.

Having been in practice for three decades, I have witnessed the digitalization, hyper-specialization, over-regulation, and dehumanization of medical care. I have seen fellow physicians retiring from the profession they once loved years earlier than they had planned after succumbing to compassion fatigue, the medical equivalent of battle fatigue known to veterans of armed conflict. It is a sad irony that while the miracles of medical research have enhanced the tools of my trade to an extent I would have thought impossible thirty years ago, the intrusion of the managed care and medical malpractice industries has created such a burden on physicians that, for many of us, the flame of passion for helping our fellow man that was ignited in our youth has burned down prematurely.

In my case, the 9,400-square-mile Adirondack Park has become hallowed ground. When I feel stressed, I climb a mountain or get in my carbon-fiber canoe, and head for one of the thousands of ponds, lakes, and streams in the Adirondacks to reconnect with nature. Personal crises seem much less important when I am standing on a mountain summit or floating across a tranquil pond, surrounded by wilderness in every direction. There I can fill my brain (and my camera) with images of the heavenly landscape. The view reminds me how insignificant we are in the grand scheme of things, and why my professional work is so satisfying.

The author on Long Lake in his Red Rocket Photograph by Patrick Sisti. Used by permission.

Later in my career it dawned on me that my Adirondack patients were at least as picturesque as the landscape, and that our relationship allowed for very natural, close portraits. And if I could write something about the patients – about their health, our relationships, or their own life stories – the impact of the visual image would be compounded. I was driven by a sense that their lives, hidden away in the folds of the mountains, testified to a dignity and courage that ought to be known beyond their own circle. If they would be willing to share the story written in their faces, I wanted to put it within the pages of a book to live on after they were gone.

As I drive over the mountain lanes, sometimes the camera captures a scene that looks like a Monet painting. Other times it is a portrait of a patient that looks like it could have been from the previous century.

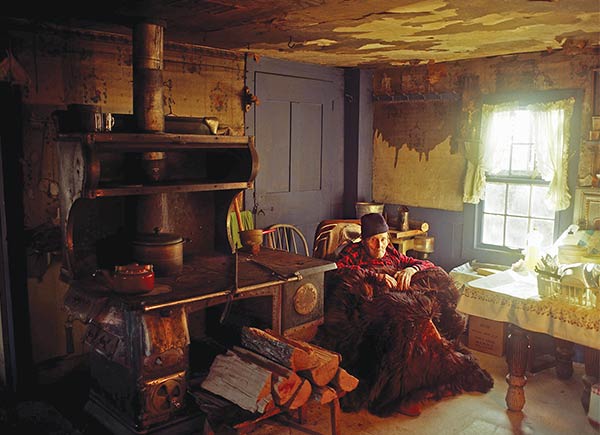

Frank Lillibridge in his Thurman farmhouse Photography by Daniel Way, unless otherwise noted.

Frank Lillibridge was the last master of Maple Grove Farm in Thurman. He grew up in the days when muscles, not machines, performed labor, and men worked on communal projects like cutting hay. His journals vividly portray a life that echoes the farm and forest seasons. In the winter he wrote of hunting and trapping rabbit, raccoon, fox, and muskrat. Each spring, the family tapped four or five hundred sugar maples. Time hardly seemed to touch the farm, or Frank himself, for that matter. An only child, he never married, and stayed true to his land and farm after the deaths of his parents.

Age snuck up on him; he came into my care when he was hospitalized for hypothermia. One cold, rainy day, he went out to dump ashes from the wood stove and fell. He lay outside all night till his neighbor found him the next morning and called the ambulance. Beyond his immediate injuries, he was so stooped, arthritic, and unsteady that I was convinced he would never return to the farm. But when offered a bed in a nursing home, he said simply, “I’ll be all right at home, and that’s where I’m goin’.” His friends took him back to Thurman, where he not only lived for another three years, but regained enough strength to go back to “cuttin’ and splittin’ a little wood.”

“I figured someone else might want to make syrup from it someday, so I left it for them, whoever they might be.”

The last time I visited him, he asked me if I’d noticed the big maple out in the yard. Of course I had; it was a giant from another era, towering over his house. “I took sap from that tree for over fifty years, and people ask me, ‘Why don’t you cut it down?’ Well, I stopped making syrup when Dad got to be ninety, and I had plenty of other trees for wood. I figured somebody else might want to make syrup from it someday, so I left it for them, whoever they might be.”

The author visiting Clarence Bateman and his son Joseph Photograph by David Slingerland

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

The two-hundred-year-old Bateman farmhouse is located in rural Johnsburg under the shadow of Crane Mountain, whose massive granite slopes shield the adjacent valley from modern life. Clarence “Bud” Bateman has lived here for eighty-odd years, sixty-five of them shared with his wife, Jean. They had nine children, most of whom have families of their own and devote what time they can to helping their parents.

Their youngest son, Joseph, has been the only one who could move in to provide round-the-clock care. A natural jack-of-all-trades, Joe has worked various jobs over the years as a logger, excavator, gravel hauler, and stone mason. But as a young man Joe had problems of his own. When I first met him ten years earlier, he wasn’t even taking care of himself. The casual observer might have dismissed him as just another bachelor mountain man in the habit of spending what little he had on alcohol. That would have been an accurate assessment – then. But he had the guts to ask for help. “I wanted to quit drinking because it was a choice of whether I wanted to live or die,” he says now in his matter-of-fact manner. He needed a safe haven to clean up his life, and his folks needed someone with dedication, determination, and a gift for improvisation. Fortunately, Joe has these traits in abundance. Once committed, Joe quickly learned the skills of a caregiver. He has been responsible for his parents’ total care for years now.

Joseph Bateman

Caring for a loved one is among the most selfless acts that can be imagined. I have seen many examples of caregivers who suffered serious physical, emotional, social, and financial hardships. Joe is acutely aware of this. Yet he continues to tend to his parents’ needs, with no predictable endpoint. “I know Dad doesn’t want to go back to the hospital or live out his days in a nursing home,” he told me, “so I’ll take care of him as long as I have to. I have no regrets – I’d do it all again – but there’s times I want to take a long walk, or step back, and count to ten, or ten thousand.… I still go four-wheeling and hunting just to get away for a while. When I get back home, I know I have to keep the firewood up, the house warm, the laundry moving.… I don’t know how long I’m gonna be able to keep this place going, but we’ll think of something.”

Anyone who understands the personal sacrifices Joe is making can appreciate the determination he must have to keep going. And he hasn’t touched a drop of alcohol in many years. He has my highest respect.

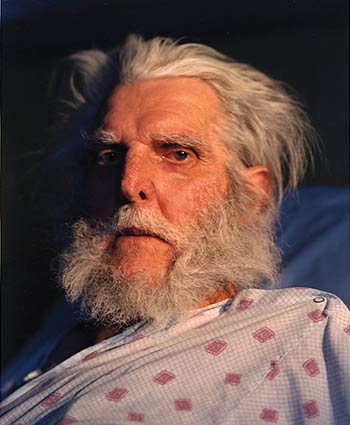

I only came to know Jesse Warren very briefly when he was hospitalized for treatment of advanced pulmonary emphysema.

Jesse Warren

When the emergency physician called me out of a sound sleep at two a.m. for a patient experiencing severe diabetic ketoacidosis, I had no idea who I was about to meet. After four hours, six liters of IV fluid, over eighty units of insulin, and a lot of work from a dedicated team, Winifred Young began to come out of her coma. As she tried to orient herself, her eyes locked on mine, and she whispered, “Are you my doctor?”

Winifred Young

“Yes,” I answered.

“What’s your name?”

“My name is Daniel Way. It’s good to see you feeling better.” With all the strength she had, she whispered, “I am feeling better. God bless you, Daniel Way.” Then she fell asleep.

Her words uplifted me, as if a window had been opened, letting in a draft of fresh air. A moment before, I had been exhausted and in need of a large infusion of caffeine, but now I felt inexplicably energized.

“My Momma always told me to see the beauty in other people. Did you know that you are beautiful?”

More conversations with Winnie left me in awe. When I learned that she had been diabetic for over half her life, yet had never suffered any of the significant organ damage so common to the disease, I asked her if she thought her joyous attitude to life might have helped her physical health. “My Momma gave that to me when I was very young. She always told me to love myself and see the beauty in other people. Did you know that you are beautiful?”

I glanced over my shoulder to see whom she was addressing, but no one else was there to take the credit. Winnie’s family has been in this area for generations. Her ancestors were among the first five black families to settle in the city of Albany in the 1880s. I have never seen her again. But I will never forget the grace she taught me.

Albert and Eleanor Alger lived along the Hudson River below The Glen, in a one-room cabin lit by a single sixty-watt bulb and heated by an ancient wood stove. In earlier years, Eleanor had made a career as a circus performer, while Albert was once a lumberjack. They took care of each other in their tiny home through years of debilitating illness. When I asked Eleanor how they survived with almost no visible means of support, she replied lightheartedly, “We’re not poor, we just don’t have any money!” That their life was simple and by modern standards, very difficult, was obvious to me. But to them, they were at home, together, in a place of welcome. They didn’t ask for more.

I would never call this work easy. But in return for my efforts, I have the knowledge that I’ve been able to make a difference in the lives of my neighbors. I have become an integral part of the community, and all the respect, affection, and appreciation I have shown my patients has been showered back upon me many times over.

Daniel Way, MD, has written three books about his work as a primary care physician in the Adirondacks. Some stories in this essay are adapted from All in a Day’s Work and Never a Dull Moment. Learn more.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

sherry lohman

Heartfelt---the stories, the pictures. Thank you!

R. Alex Chamberlain

Thanks for this. I attended scout camp near Saranac (Camp Massawepie), and went to college north of the "Dacks" in Canton. I have explored many of those lakes by canoe and caught both fish and black flies, nibbled wild blue berries while listening for bears, and the scents of the area still linger. I have been a hospital chaplain for 32 years and resonate with the idea that the pursuit of healing takes many forms...and seen how a simple touch from a physician or nurse can evoke such deep feelings from patients. Bless you in your continued work.

Dan Grubbs

Having read this piece it brought back to mind my old family doctor. A quick anecdote about Charles A. Longo, M.D., surgeon. Doc Longo was a no-nonsense practical family doctor who was also a general surgeon. He was my doctor as I grew up and he became my children's doctor until his death. While I was in the U.S. Air Force stationed in the same area where I grew up, my infant son had a bad case of diaper rash. The military medical doctors gave us this powder and that cream and nothing worked. Then they advised us to just let my son run around bare. No progress. Finally I was frustrated and visited my old family doctor, Doc Longo. He looked over my son and in 15 seconds was writing a note on his prescription pad and told us to take it to the pharmacist in town who will know what it is because Doc Longo asks the pharmacy to keep it in stock. We went to our local Walgreens with slip of paper in hand and handed it to the pharmacists who came out from behind the counter and pulled a jar of hoof dressing off the shelf. We were stunned. Hoof dressing, as in for horses and cows? Yes, the pharmacist assured us this is exactly what Doc Longo wants you to use. We took it home and followed his instructions and in two days the diaper rash was nearly gone. Many times Doc Longo applied practical and wise medicine helping my parents' family and later my own family. When government got involved, it ruined it and now that kind of "good ol' horse doctor" is very rare to find. By the way, ol' Doc Longo's medical records for every patient was a simply 5X7 index card he kept in a wooden box.

Kim Moir

This article brought refreshment to my soul this morning. His respect and dignity for these individuals shows that he captures the good in others and by doing so, enriches his own inner life.

Bob Taylor

Lovely article. The doctor may not have made much money, but he's led a rich life, indeed.

CHRISTINA MANWELLER

How beautiful, to share the gift for healing in such a compassionate manner. I wish more doctors could return to a simpler, more humane way of practicing. Thank you for sharing this beautiful, humbling story. Reminds one of what it means to be human.

G.M. Neher

Thanks for sharing Doc. As a child of the Catskills the people you write about remind me of my people here. I think of them as my people as I hope that my people think of me as theirs as well. Wonderful words and great insights. Thanks for giving us you and treating us "patients" as the humans we are. God bless.

Edie Reynolds

Beautifully written. Dr Way. You have not lost the principles of your training. Your synapses are still connecting your heart with your brain. God bless you for your years of service. What a colorful practice you have had. Thank you for your words and pictures.