Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Carry Me

-

The Soul of Medicine

-

Readers Respond: Issue 17

-

Family and Friends: Issue 17

-

The Hunter

-

Beyond Racial Reconciliation

-

Science and the Soul

-

Money-Free Medicine

-

Patient Perspective

-

On Being Ill

-

On Eternal Health

-

Adirondack Doctor

-

Christ the Physician

-

What’s a Body For?

-

Begotten Not Made

-

The End of Medicine

-

Perfectly Human

-

Let Me Stand

-

All Sorts of Little Things

-

The Measure of a Life Well Lived

-

Siegfried Sassoon’s “Before the Battle”

-

Editor’s Picks Issue 17

-

Our Task Is to Live

-

To Be Plucked by a Strange or Timid Hand

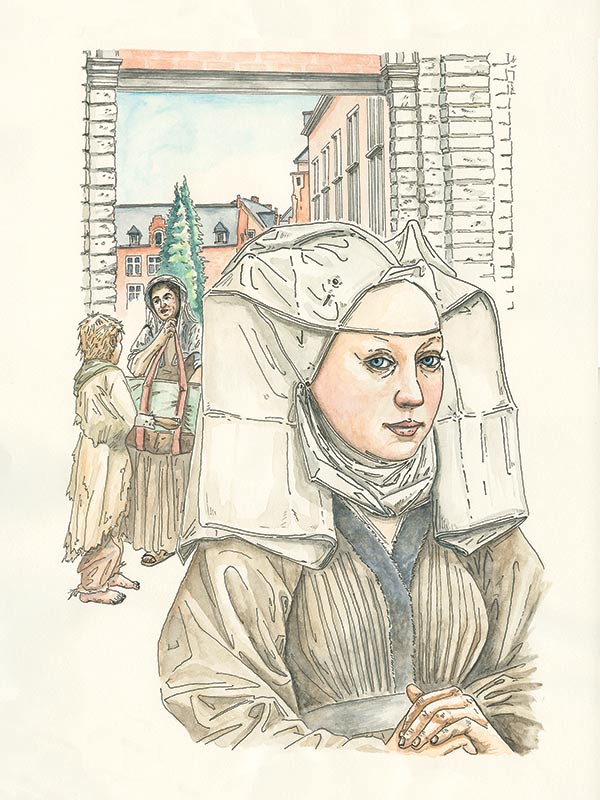

“Men try to dissuade me from everything Love bids me do. They don’t understand it, and I can’t explain it to them. I must live out what I am,” wrote Hadewijch, a thirteenth-century woman from Antwerp, Belgium.

Hadewijch was a member of the Beguines, a medieval renewal movement of women – there was a brother movement for men known as the Beghards – that formed around 1200 in Flanders and lasted until 2013, when Marcella Pattyn, the last Beguine, died.

The Beguines were lay women who formed communities of worship and mutual economic support. While some beguinages were loosely aligned with religious orders, they remained independent from the hierarchical and financial structures of Europe’s medieval church. While renowned for their zeal in prayer and their charitable works, which made them indispensable in many towns, the Beguines were often under suspicion. Several were pronounced heretics, and even executed, for their mystical teachings or for “insubordination.”

Nevertheless, the movement grew. Drawn by new employment opportunities in growing industries, many women came to cities for employment. There, cut off from the traditional social network of extended families and tight-knit rural villages, they turned to beguinages for support and fellowship. Others, drawn to a life of apostolic service, came from upper-class backgrounds. Some were widows or fleeing abusive marriages; still others were rescued from a life of begging or prostitution.

Jason Landsel, The Beguines, after Rogier van der Weyden’s Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1435).

The Beguines practiced a simple lifestyle, but still owned property individually and communally. Members were free to leave the community at any time. Beguinages differed in size, from a single house with a few women to a walled village with over a thousand inhabitants. Communities were frequently guided by a magistra, a woman of eloquence and spiritual insight.

Beguines were committed to vita apostolica – the “apostolic life.” French historian Jaques de Vitry described beguinages as “hospices of piety, houses of honesty, workshops of holiness, convents of the right and devout life, refuges of the poor, sustenance to the wretched, consolation to those in mourning, refectories for the hungry, comfort and relief for those who are ill.” Beyond these acts of mercy, the Beguines carried out an energetic street ministry, with plays and theaters that urged audiences to repent and turn back to the source of their faith.

The movement produced numerous visionaries and mystics – women like Marguerite Porete, Mechtild of Magdeburg, and Hadewijch – whose visions, prayers, poems, and spiritual practices were documented and survive as inspiration to this day.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Love is always new!

Those who live in Love

Are renewed every day

And through their frequent acts of goodness

Are born all over again.

How can anyone stay old in Love’s presence?

How can anyone be timid there?

– Hadewijch

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Deborah

I enjoyed this article on the Beguines very much. It just ended way too soon. I look forward to learning more about them in my continued reading on the subject. What wonderful role models for we women to aspire to.