Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Giving Your Children Your Words

-

Book Tour: On Being a Good Ancestor

-

Ten Theses on Intergenerational Stewardship

-

Inheriting Mental Illness

-

Yearning for Roots

-

Fear of a Human Planet

-

Reviving the Village

-

Is There a Right to Have Children?

-

The Stranger in My House

-

The Sins of the Fathers

-

My Father Left Me Paperclip

-

Decoding the Bible’s Begats

-

The Name of My Forty-Sixth-Great-Grandfather

-

Somewhere in Chessington

-

Singing the Law

-

Desiring Silence

-

Uncle Albert

-

Soldier of Peace

-

Two Crônicas

-

Poem: “The Revenant”

-

Poem: “L’esthétique de la Ville”

-

Poem: “When You Pursue Me, World”

-

Gazapillo

-

Editors’ Picks: God Loves the Autistic Mind

-

Editors’ Picks: Damnation Spring

-

Editors’ Picks: Life between the Tides

-

The Faces of Our Sons

-

Remembering Tom Cornell

-

Letters from Readers

-

Monica of Thagaste, Mother of Augustine

-

Covering the Cover: Generations

-

A Legacy of Survival

Daughter of Forgottonia

In a left-behind corner of Illinois, Edna Eberlin made her farm a home for a sprawling multigenerational family. It was never easy.

By Liz Schleicher

November 25, 2022

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Some people are born into money. Some into a famous name. Others, a royal bloodline. For the Eberlins, our heritage is a beautiful piece of land: We were born in the southernmost reaches of Forgottonia.

Forgottonia is a rugged sixteen-county region of western Illinois, penned in by the Illinois River to the east and the Mississippi to the west. It was named so some sixty-odd years ago, as a form of political protest and a plaintive reminder to the economic powers in the rest of the state: We exist. We deserve your attention.

No one listened.

Forgottonia comes to a narrow southern peninsula at Calhoun County, Illinois, (population, 4782), above the confluence of the mighty rivers. It is the wildest, most beautiful, most hidden place that exists east of the Mississippi. To know the history of my family, it is first necessary to know the land. Our story cannot be told without it. We plant and harvest. We dig in the loess and cut the timbered hills. We hunt the waterways and tie our boats on the banks. We call our county “The Kingdom,” after the words of a local poem:

Verdant hills and valleys resting

Between the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers:

An uncommon area.

Quietly proud of the heritage and achievements of our people.

God’s little kingdom and precious jewel.

The Eberlin family property today, bordering the Mississippi river. Photograph by David Eberlin. All photographs courtesy of the author.

We believe we are his subjects, given a mission to tend and keep a corner of the world no one else cares about. Calhoun County, even more than the other fifteen, has always been forgotten. Even the glaciers overlooked it as they ground the rest of the state into a flat and expansive prairie all those thousands of years ago. The county is a geological “driftless area,” a mere thirty-seven-mile-wide finger of farmland and forest. It resembles the Missouri Ozarks or the more famous Driftless landscapes of Wisconsin and Minnesota. There are wild, desolate flood plains, washed flat by the powerful meandering of the rivers. These abruptly give way to limestone river bluffs three hundred feet high and a dividing ridge of steep hills and deep forested “hollers.” Farther south, the hills become gentler and more rolling for a time, covered with rich soil perfect for orchards and cornfields. Much of the peninsula is a karst landscape, pocked with caves, springs, sinkholes, and creeks that dive deep underneath the ground on one property only to reappear a few miles away.

My family’s relationship to this land also runs deep. At times, this connection has trickled almost out of existence, as disregarded as Forgottonia itself. But by the work of one heroic woman, not even heir to the land by her birth, our farm and our family have been preserved and renewed for a new generation, bursting forth like water from the rock.

For exactly 150 years, my family has lived in this beautiful place, up and down the east bank of a steep forested hill in the south of the Kingdom, not far from the Mississippi River. In 1872, a war-weary Frenchman named Blasius Eberlin and his wife, Adeline, bought forty acres of farmland at the bottom of the hill. They raised eight children and buried two: their first little boy and their only daughter. Their remaining boys grew to adulthood. Several left for the West, inheritors of their father’s wanderlust. But a few stayed home, including my great-grandfather Henry, who married a neighbor girl named Mary in 1904. They also farmed the land and had eleven children, again mostly boys. A few left. But the majority, including my grandfather Harold, settled down on the land.

The Henry and Mary Eberlin family. Bottom, L to R: Raymond, Arthur, Mary, Henry, Richard Top, L to R: Harold, Eddie, Cassie, Lucille, Delores, Viola, Charley, Abe.

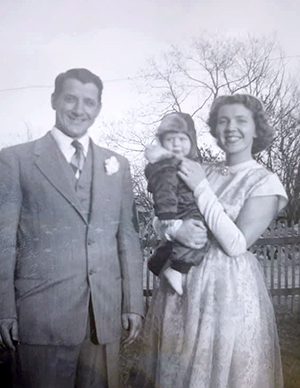

In 1948, twenty-six-year-old Harold was a tall, strong war veteran, charming and self-assured, with wavy dark hair and piercing blue eyes. He was known among his peers as a keen baseball player, a fantastic dancer, and a natty dresser who loved to have a good time. After the harvest that year, he married Edna Kronable, a curly-headed eighteen-year-old farmer’s daughter from a German Catholic settlement to the north. She was sweet, hardworking, and devout, came from a family equally as large as her husband’s, and shared his love of farming and sports. The match seemed perfect. The couple settled in an old cabin in a deep valley on Eberlin family land. Edna embraced her role as a farm wife.

Elsewhere, Americans reveled in postwar prosperity and modernity. But life for poor farmers in the Kingdom was not much different than it had been for the past half-century. Harold and Edna’s first home lacked insulation, plumbing, and electricity. Edna’s chores included feeding the wood stove, churning butter, doing laundry in a galvanized metal tub, and ironing every piece of clothing from suits to underwear. She milked cows, butchered chickens, made quilts, and after a few years of anxious waiting, started to sew baby clothes. The new generation of Eberlins began to arrive in 1951. While the couple was able to give their first son the privilege of a hospital birth, they had to drive forty miles to get there.

Edna worked at all these tasks with a physical strength and endurance that would outstrip most modern men. But her real devotion was to the land and all the good things that grew there. In the early 1950s, the Eberlins moved uphill, purchasing a farm from their cousins with the help of the Federal Land Bank. This was a major expansion of the family’s holdings. Under Edna’s direction, the land burst into blossom. The grounds around the old cabin were converted into fields for growing the family’s potatoes, orchard fruits, and other staple crops. Edna chose a football-field-sized space just outside the newly bought farmhouse as the site of her kitchen garden. From early spring to late summer, neatly tilled rows of cauliflower, radishes, peas, green beans, tomatoes, peppers, sweet corn, beets, and melons flourished in the sun, as well as old German favorites like cabbage and kohlrabi. On two sides, the garden was bordered by fruit trees purchased from the Stark Brothers mail-order nursery. To the west stood a windbreak of pines. The south side was crowned with a huge strawberry patch that was the pride of the farm. Edna often woke up with the sunrise to weed and mulch and harvest, untangling runners and gently resetting them with the patient grace of Our Lady, Undoer of Knots.

Harold and Edna's first house together.

As Edna cultivated the land, it cultivated her. She led an ever-growing brood of half-wild children deep into the woods to hunt morel mushrooms and wild blackberries, ripe persimmons and black walnuts. She taught her daughters how to stir apple butter and make sauerkraut and store potatoes down cellar. She and the other adult women of the clan oversaw butchering time: making sausage, rendering lard, canning beef, and even saving poultry feathers for pillows. Increasingly, she used the green, repetitive peace of the garden and the familiar work of each season to steady herself. Around her, the Eberlin family was aflame.

The same year that marked the joyful birth of Harold and Edna’s first child also began a long period of suffering for their family. Mary, Harold’s mother, had suffered with diabetes for years. It claimed both her legs, confining her to a wicker wheelchair. By 1951, it had also taken her mind. She died in the St. Vincent Sanatorium in St. Louis, Missouri, a victim of diabetic psychosis.

Mary wasn’t the only one who was deeply troubled. Underneath his famous swagger and charm, Harold too was broken. He had always been the spoiled baby of his own family, shielded and literally hidden away from hardships or consequences by his doting older sisters. But they couldn’t shield him from the draft, and he entered the Army in 1944. As an infantryman and “runner,” he endured a record 144 days of continuous combat in France, Germany, and Austria. Much of the fighting took place in Alsace, the very homeland his grandfather Blasius sought to escape. Harold credited his faith, specifically the rosary, with saving him.

But the rest of the family was not safe from him. Harold’s hot temper and profound trauma made the Eberlin home a perilous place. He drank away his memories, and as he drank, he became violent to both his wife and his children. Today, we might call this PTSD. In the 1950s, it wasn’t talked about at all.

For Edna, a devout Catholic, divorce was not an option. She believed wholeheartedly in the teachings of her faith as they were interpreted by her community – and her community hardly knew how bad things really were. Her parents expected her to endure in the name of the sacrament of matrimony. Her older sisters-in-law, who had always protected Harold, continued to enable him. Her neighbors and friends, for the most part, saw a fun-loving guy with a pretty wife and a passel of kids who showed up at Mass every Sunday, neat and pressed, no matter what. Even in an ocean of extended family, Edna was almost alone. She would have been if not for Abe and Delores.

Abe and Delores were Harold’s big brother and little sister, closest to him in age at the tail end of their large family. Neither was married, and both continued to live at the bottom of the hill on the original Eberlin homestead with their parents. After Mary died, it fell to Delores to act as the matriarch of the extended Eberlin clan. She looked after her aging father, cooked for her brothers, and cared for the homestead. In the middle of the 1950s, she also became caregiver for her brother Arthur, who suffered a traumatic brain injury in a fall from the family’s hayloft. Abe worked in construction to raise money for the household, but they lived sparingly and were able to subsistence farm for most of their needs. Their house became a place of refuge for the Eberlin children, who were shuffled down the hill to the homestead whenever trouble brewed. Jolly, comforting Delores bought them presents, told ghost stories, and expertly sewed the girls’ dresses. Tough, quiet Abe hunted and fished with the boys, took them to baseball games, and gave them the affirmation and attention their father could not. Together the family thrived, against the odds of poverty and abuse.

Harold and Edna with their first child.

Eberlin children kept coming, with no more than two and a half years between any of them. Remarkably, they were all healthy. In 1962, Edna gave thanks to God for this gift by naming a son after Saint Gerard Majella, patron of expectant mothers. She leaned on her faith more and more as her sons and daughters grew, keeping her rosary under her pillow and praying from the back of a different holy card each night. Infused with a supernatural unflappability, she seemed afraid of nothing – not her rowdy children’s frequent injuries and mishaps, not the family’s financial circumstances, not even her husband’s violence. Harold had been the soldier, but Edna was now the general. She led the Eberlin family with quiet faith, unmatched work ethic, and continued loyalty to the land and its fruits.

Harold remained employed, but his care for the farm dwindled as his alcoholism increased. Again, Edna took the lead, this time aided by her older children. Her oldest daughter managed childcare and housework while she and her elder sons planted and harvested. The family’s table was always full, and a total of twelve people never went hungry, even if their diet sometimes consisted of squirrel and potatoes. The children never felt poor. They had food and clothes and even Christmas presents (thanks to Aunt Delores). They had farm animals and pets to care for, from milk cows and hogs to a pack of mischievous beagles. They had woods and creeks to hunt and roam in. They had each other.

They also had the land, now well and truly theirs. In the late 1960s, the family paid off the lien on their home and farm. They added their first indoor bathroom and an extra bedroom for the children. They were full of pride. They planned their first family vacation, to the Du Quoin State Fair in southern Illinois.

They never made it.

In 1972 Aunt Delores, who had no driver’s license and walked everywhere, began to complain to Edna about a sore on her foot that would not heal. By that time, she had organ damage from advanced diabetes. She underwent a series of amputations, then left the old Eberlin homeplace for the last time. She was moved into her sister’s small and crowded home. Dreams of family vacation were laid aside as all the nieces and nephews turned their attention toward their ailing second mother. Delores died a month later of the same disease that had killed her mother. She was only forty-seven years old.

Edna and the children were left without their beloved confidante and supporter. They held steady, but some of the childlike joy and magic had gone out of their lives. It was the end of an age.

In faith, Edna continued on, shouldering the crosses of abuse, addiction, and poverty and lifting with all her might. Harold’s problems continued to worsen as the years passed, and in the mid-1980s, he left the farm for good and moved to another village about ten miles away. Edna continued to pray for him and care for him from afar. With a grace that seems foolish to the modern mind, she forgave him seventy times seven times for the pain he caused her. She told her family that the night Harold died in 1997, she had experienced a vision of him at the foot of her bed, asking one last time for her forgiveness. Imitating the Jesus she loved so much, Edna accepted the apology of her husband’s departing spirit.

With a grace that seems foolish to the modern mind, she forgave him seventy times seven times for the pain he caused her.

Thanks to the support of their mother and uncle, the children continued to flourish into adulthood. They became award-winning student athletes, graduated from high school and college, and began to form families of their own. In the Kingdom, both the farm and the name Eberlin became synonymous with Edna, a woman related only by marriage. She was the bearer of the banner which Blasius Eberlin gave his descendants to carry all those years ago, the banner that Harold had laid down. Edna was now in the eyes of the law what she had been in reality for the past four decades – the true heir of the Eberlin family and the farm.

The meek had inherited the earth.

Through these years of spiritual, physical, and mental trial by fire, Edna’s faith did not waver. Instead, it became stronger. She was a frequent Mass-goer and an avid reader of Catholic magazines. She attended Al-Anon Family Groups. She prayed her rosary every day and was devoted to Our Lady of Fatima, whose statue presided over the farmhouse living room, surrounded by photos of smiling grandchildren. Her measure of love and faith was so full, it spilled over, blessing the lives of everyone around her. She showered her family with what little material wealth she possessed. But more importantly, she was a fount of charity and simple wisdom. Friends and strangers alike commented on her willingness to listen to their problems without judgment and the aura of peace that seemed to surround her presence.

The farm, too, became an oasis of comfort and renewal. Children and grandchildren came and went constantly. There was always someone in the kitchen – frying burgers in a pan, slicing peaches, stirring Kool-Aid or Nestea in a glass pitcher marked BEER. There was always someone outside tilling the garden or hunting squirrels or playing with the barn cats. There was always someone perusing a sales circular or starting a game of Yahtzee at the dining room table. Always at least two people arguing, both of whom insisted they were not arguing. Always a pile of curly-headed babies asleep on a homemade quilt in Grandma’s darkened room. And despite the din, there was always someone asleep in the middle of the living room floor. Mostly they visited just long enough for a nap and a bowl of ice cream, but in times of trouble, they might remain at the farm for months. No matter how long the stay, Edna loved to welcome guests and host family gatherings. Her tiny farmhouse seemed to expand through the force of love alone, stretching to accommodate more than fifty rowdy people for Thanksgiving or Christmas.

In the early 2000s, an aging Edna was asked by her daughters if she’d like to go to a nursing home when the day came that she would need full-time care.

“Over my dead body,” she replied curtly.

In 2011, at the age of eighty, Edna Margaret Eberlin died in a fire that consumed her home and almost all of her personal possessions. Her beloved land was the only thing that remained.

It is impossible to understand why some folks live lives of ease and pleasure while others struggle for their daily bread. It is incomprehensible that someone so beaten down by brokenness could spring back like a stubborn flower, again and again, with nothing but grace for the feet that trod on her. It is unbearable that such a beautiful life be snuffed out, painfully, with no fanfare, no one to blame, no time to say goodbye.

But it is extraordinary that a simple farm wife, uneducated, poor, and without power, could bring such an abundance of grace into the world through the simple work of her hands. If Christ is the River of Life, Edna was a branch of that holy stream, bringing plain, sweet, healing water to all those who gathered around her in a world of fire. That branch still continues to flow through her descendants, bubbling through our lives just like the creeks on the land she loved.

Like their mother, many of Edna’s children inherited her work ethic and deep devotion to farming. Six took up agriculture as a career. Two are avid home gardeners. Edna’s eldest daughter was heir to Aunt Delores’s fine skills as a seamstress. Many inherited the Eberlin scourge of diabetes, but miraculously, all of her children escaped the Vietnam draft and another generation of war.

Edna’s death marked the end of another era, with no one living full-time on Eberlin holdings for the first time in over a century. But the land continues to be farmed – it is still the site of fields of corn, wheat, soybeans, timber, gardens, and peach orchards. In 2015, Edna’s oldest son and his wife purchased the adjoining ranch, increasing Eberlin family land from the original homestead to a nearly two-mile swath of hills and hollers ending on the banks of the Mississippi River. Edna’s home site and the new ranch are now the twin centers of extended family life. We still get together there – not just for work, but also for wedding dances, holiday parties, and mushroom hunts. There are twenty-five sixth-generation Eberlin babies to date, and we are still growing in love led by the enduring example of our mother and grandmother. We regard her as a family saint and continue to ask for her intercession. In 2021, she received her first namesake. The name Edna means “renewal” and “delight.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Claire Hagen-Fleck

My family also stretches back generations in Calhoun: my dad's people mostly rest in the Meppen Catholic cemetery, and my mom's people are in the Hardin cemetery. It was lovely and poignant to read this, and it made me long for Calhoun County peaches!

Caroline S

Thank you for your brave and reaffirming story. In the world we live in today it is good to be reminded that faith, kindness and goodwill are strenghts rather than weaknesses.

Burl Self

Thanks for reminding me that God’s Creation is woven into every facet of our being.

Susan

God bless all of the dependents of this family. What a wonderful and heartwarming story.