Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Inheriting Mental Illness

-

Yearning for Roots

-

Fear of a Human Planet

-

Reviving the Village

-

Is There a Right to Have Children?

-

The Stranger in My House

-

The Sins of the Fathers

-

My Father Left Me Paperclip

-

Decoding the Bible’s Begats

-

The Name of My Forty-Sixth-Great-Grandfather

-

Somewhere in Chessington

-

Singing the Law

-

Desiring Silence

-

Uncle Albert

-

Soldier of Peace

-

Two Crônicas

-

Poem: “The Revenant”

-

Poem: “L’esthétique de la Ville”

-

Poem: “When You Pursue Me, World”

-

Gazapillo

-

Editors’ Picks: God Loves the Autistic Mind

-

Editors’ Picks: Damnation Spring

-

Editors’ Picks: Life between the Tides

-

The Faces of Our Sons

-

Remembering Tom Cornell

-

Letters from Readers

-

Monica of Thagaste, Mother of Augustine

-

Covering the Cover: Generations

-

A Legacy of Survival

-

Daughter of Forgottonia

-

Giving Your Children Your Words

-

Book Tour: On Being a Good Ancestor

Ten Theses on Intergenerational Stewardship

Our family has been stewards of land for centuries. Here are lessons we’ve learned about how to care for it sustainably.

By Prince Michael zu Salm-Salm

December 2, 2022

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Prince Michael zu Salm-Salm is the heir to lands in southern Germany and the managing partner of Salm-Salm & Partner, an asset management company serving institutional clients, families, and foundations, which he founded in 1990. As well as convertible bonds and other financial assets, the company focuses on the acquisition and management of forests and farms for institutions and families in the United States, New Zealand, and Central and Eastern Europe.

On behalf of his family, the company holds around 450 acres of forest and extensive vineyards, as well as a winery that is Germany’s oldest.… In addition, the Salm family has partnered with the Boscor Group, one of Germany’s largest service providers in forest and land management, to form the First Forest Company, an association of eight families with forest holdings in Germany that amount to more than twelve thousand acres in total.

The company Prince Michael founded has publicly committed to advancing ecological sustainability according to Christian principles. Since 2012 it’s been a signatory to the UN Principles on Responsible Investment and has been committed to helping meet the Paris climate targets in the way it manages mutual funds. The company declines to invest in nuclear power, embryo research, fracking, military weapons, abortion, pornography, and gambling, or in any other company known to violate the rights of workers or children.

“In all our decisions,” the company’s prospectus says, “we let ourselves be guided by our Christian convictions.… Not everything that promises added value is also ethically correct and leads to long-term success. We only do what we are – in good conscience – convinced of.” This vision extends to the vineyards and winery as well. “We want a company in which people work, but also develop spiritually,” the winery’s website explains. “Work and prayer should not be separated from each other, but should overlap.”

The prince is presently the vice president of the European Landowners Association, president of the Friends of the Countryside, and active in the Christian Democratic Union party. As the representative of an old Catholic family married to a Protestant – his wife of more than four decades, Princess Philippa, comes from the Castell-Castell family, one of the first ruling houses to introduce the Reformation in Germany – Prince Michael is also involved in many ecumenical efforts. —The Editors

Ruins of the twelfth century Dalburg Castle, destroyed by the French in the nineteenth century. All photographs courtesy of the author.

I come from the village of Wallhausen, on Dalberger land, thirty kilometers west of Mainz, in the Rhineland-Palatinate. My grandmother, the Baroness von Dalberg, was the last to carry the name, but the family goes on. The Dalberg property, which I am permitted to manage, comes from her. My family is now in the thirty-first generation in the same place, on Dalberger land. It is there that we have our home and make our living, managing our vineyards and forests.

The wine author Hugh Johnson once said to me, “A thousand years, always in the same place. Have you never been bored there? How did you manage to stay?”

We have never been bored. We have been occupied at least seven times – by the French, Swedes, Spaniards, Austrians, and Prussians. Three times we have been evicted: once by the Swedes and twice by the French. But we always came back.

We didn’t do it on our own. This was only through God’s help and grace – it was and is no merit of ours. We are grateful and glad that the locals never drove us away.

Since my mother died five years ago, we’ve been three generations on the farm; me and my Philippa, our eldest son Constantin with his wife Friederike and their five children. We have twenty-five grandchildren, and all of our six children are happily married to spouses who believe in Jesus.

My wife is the heart and the stable anchor of our family; the same applies to all mothers. My two sons run the day-to-day business. The next generation is on deck. Constantin is the managing director of our finance company, and Felix, his brother, is responsible for the winery.

From whom have I learned about sustainability, nature and God?

Most of it, I learned from my parents, my grandparents and my in-laws, and they learned it from theirs: from the family. What is it that lasts, what resonates down through the years, of those who came before us? What did they teach us?

I want to share with you ten tenets of the ancestors for sustainable business, living, and prospering.

1. We are only stewards

… and everyone has a part to play.

Everyone must do his or her job. I am only the manager of the family property in my generation; legally the owner, but actually only the steward. It is our job to preserve, protect, and pass on.

So I have only borrowed the property, not inherited it. I am a link in the generation chain. May this link not break in my generation and tear the chain.

2. We must value each family member

… and learn family cohesion.

On farms, as in family businesses, business succession is often structured as follows: the eldest son (and if there is no son, then the eldest daughter) takes on the task and inheritance, and the others do without, or take a smaller portion. This has proven to be useful so that the family and the land can continue to be bound together, and so that the work can go on. This heavy sacrifice of the siblings can only be borne if they are respected and honored in a special way. It is of course a duty that all children receive a good education. As well, every family member must be valued, and must know that if necessary, they can count on help from the family, and especially from the heir, the successor to the title and the land.

Vineyards in Wallhausen Felseneck/Breitwiesen, cared for by the Dalberg family for over eight hundred years.

3. The ancestors set the example

… in appreciating and preserving our places, our homes.

Fixed places are used for orientation, to help us know where we are in the world. Home creates trust. That is why we keep our listed house, even if it is difficult and expensive. That home ensures stability and creates culture. It serves the place and the region. We open our house regularly in hospitality, at parties for our colleagues in the village who present their wines to the public.

Fixed places create traction; they keep us grounded. Real estate should never be an end in itself, but serve people.

4. We must learn from history

… to take responsibility in the world, in society and in politics, to promote the common good.

My parents drew the conclusion from the Nazi era that it is essential that everyone be involved in the body politic, that everyone must take appropriate political responsibility, aiming in their public work not to serve their own private interests but the general welfare. Here the fate of whole peoples and countries is decided.

Learning from history means, for example, knowing that Germany has always been a country of refugees: that is, a country of refuge. Germany as such emerged from the migration of peoples. Everyone in Germany has at least one parent, grandparent or great-grandparent who suffered the fate of a refugee.

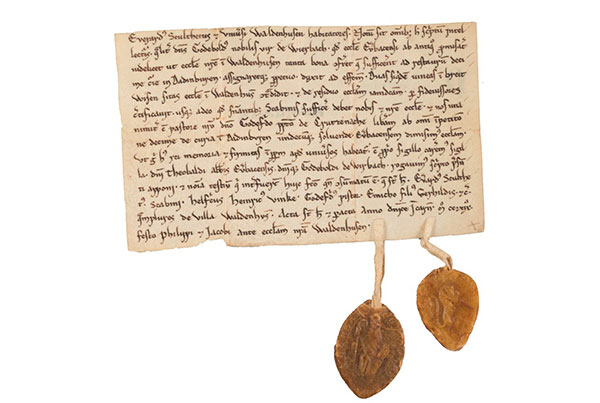

A property deed, AD 1218, documenting vineyard sites owned by the Dalberg family.

Germany caused one of history’s largest waves of refugees during the Second World War, when up to 40 million European “displaced persons” fled their homes. At the end of the war, Germany took in more than 12 million refugees, who found a new home here. We carry the so-called refugee issue in our genes. Refugees are our purpose, challenge, and task, and can be a blessing.

The great task for our generation, to build and secure the European house, can only succeed if each individual contributes his or her uniqueness. Germany is a beautiful country. Our mark is diversity, not simplicity; diversity, not uniformity, federalism instead of centralism. No country in the world imports and exports as much as Germany; we live on cosmopolitanism.

5. We must take responsibility for the natural world

… and delight in it.

The buzzword today is “sustainable development.”

What does sustainability mean? According to a widely-adopted model, sustainability is assessed in three dimensions:

Economic

We must not harvest more than grows back; we must not eat up our capital. This is what Hans Carl von Carlowitz first postulated three hundred years ago. The word “sustainability,” Nachhaltigkeit in German, was first used in something like its modern sense in his Sylvicultura Oeconomica (1713), in which he articulated the principle that one must only cut as much wood as one had planned to replace through reforestation projects.

This still applies today, and it applies beyond forestry. It is the principle of the so-called “Swabian housewife” who does not spend more than she earns. How good would this principle do countries of the European Union! We could have avoided the sovereign debt crisis. How good would it be to adhere to this principle in the management of our national pension fund, and our social-welfare systems!

Ecological

We live, in the Western world – on the whole globe – beyond our means. We pollute the environment. We plunder finite resources.

Our mission, on the other hand, is to pass on the globe – God’s creation – to our children in at least as good ecological condition as we have received it; ideally to increase the fertility of the earth, and if not that, at least not to lessen it.

We are not doing justice to this aspect of the “creation mandate.”

The picture I have in mind is of my grandfather, who kept every piece of paper in order to use it again. He was furious about air pollution, which has been a major problem in Germany, though things have improved. He made me aware of my responsibility for nature and its beauty at an early stage.

That is why today we manage our forests naturally, rather than according to a plantation model, and why our vineyards are ecologically friendly; it is why I promote renewable energy.

Social

Again, let me give you just one picture: When the wife of an employee of our family, the mother of his four children, died in childbed with their daughter Monika, it was a matter of course for my parents to take Monika into our family. All the children did their homework with us. On Saturdays, as was customary at the time, on washing day, we were bathed together in the tub. We were taught social responsibility from childhood.

Social cohesion, community, must be cultivated.

Sustainable family forests in Wallhausen and Dalberg.

6. Honor work and the worker

… and learn the value of hard work.

My brothers and sisters and I weren’t spoiled at home. There was only a small amount of pocket money. My wife and I did the same with our children, and that was a good thing. Those who want more have to work, was the motto.

With the many interns that I have been able to introduce into professional life, I have observed time and again that the spoiled, those with too much pocket money, have a hard time. Working in the vineyard, milking the cows on the farm, was good for me. That gave me some of the mindset of an entrepreneur, and it did the same for my children.

7. Build on cooperation and partnership

… because together we are strong.

Many local farmers work very well with their neighbors. In Germany, a Gesellschaft bürgerlichen Rechts (private partnership) is often set up for joint management. Success is achieved in a team.

“Goodness comes from goods.” That is why nine winegrowing families, from nine terroirs, with nine top wines, have founded the cooperative Die Güter. We feel comfortable working together, and we are doing well.

Good, trusting partnerships complement the strengths of the individual and compensate for the weak points. The crucial thing is the person: his decency, his ability. In the creation story we read that man was created in the image of God. That is his dignity. Only as we work together in all our variety do we come to reflect this image more perfectly. That is why solidarity is so important for sustainability.

8. Learn from nature

… because nature serves as a model for sustainability.

The wise ancients knew this and taught it: the forest itself can be our role model. From it we learn the truth of the old saying: “die Bäume wachsen nicht in den Himmel,” “The trees do not grow into the sky.” In other words, we can’t always have infinite growth: we must be prudent.

How good it would be if some people understood this before the financial crisis of 2008 and other such bubbles, and had controlled their greed! You don’t get rich from the forest, because you can only extract what grows back every year. But a family, a community, can keep themselves well with it, through the generations.

We rely on natural silviculture. Here nature itself sows. The young trees grow up under the protection of the old. They don’t need to be planted. In this way, a mixed forest is promoted. This is an approach that we also take with our asset management at Salm-Salm & Partner: we don’t put all our eggs in one basket.

We can take lessons from the vineyard as well: we can work as hard as we want, but if the weather isn’t right, all efforts are in vain. Realizing this makes you humble. We learn that not everything is in our control, but that there is a higher law there, in nature: the law of God; his providence overrules all our plans.

Realizing this prevents hubris. In my lifetime I have experienced weather-related crop fluctuations : In 1981 we harvested eight hundred liters of wine per hectare of vineyard, and in 1982, over ten thousand liters on the hectare.

Industrial companies can hardly cope with such fluctuations, because they expect short-term and consistent profits; their commitment is to profit from their harvest; they are not committed to the work, to the vines, to the land. But we must plan for the long term, prepare for crises, for exceptional situations, because this is the only way to ensure sustainable survival.

In the end, however, despite all the necessary attempts at crisis prevention, our lives are ultimately in God’s hands.

Dalberg descendants walk in the family forest which is maintained by sustainable silviculture.

9. Stewarding creation is a wonderful task

… and to find work that is deeply human is a blessing.

Wine is a tremendously complex and beautiful way of living, working and enjoying.

Compared to other industries, it only brings in small profits, requiring high capital and labor input, but you are on the move holistically. Your work makes sense; it is complete. Winemakers grow grapes, process and refine them into wine and market them globally, offering this goodness to the world.

The purity of the product, when it is grown and prepared in the customary way, its beneficial properties for health, for intellect, for one’s spiritual life and love life, make this gift of God the culmination of human work.

The forest too offers a satisfying and joyful living. When I step into it, I feel awe. This forest – it is simply the most beautiful part of God’s creation in this country, which has been preserved in something like its original form and entrusted to us humans.

A forest is a wonderful ecosystem. The trees produce healthy air, they purify and store water, and they are both a source of food and a means of production.

But it is up to us to manage the forest. Carbon dioxide is bound – sequestered – as trees grow; in a primeval forest, those trees would release the bound carbon dioxide again when they die and the trunks fall apart. But it is stored in every piece of wood that is built into furniture or roof trusses. As we make the built world, our human world, we do well by the natural world also.

Germany is the country in Europe with the largest supply of wood. Much more wood grows back every year than is harvested. The forest farmer must be a humble person by nature: patient, not seeking to enrich himself quickly. He only sows and plants what his grandson can harvest at the earliest.

These are the lessons of sustainability. And when it comes to sustainability, family businesses in the countryside and forest are the ones that can and must lead the way: we are the ones who take care of the countryside!

Castle of Wallhausen, the family’s living and administrative center, including a wine cellar of the Salm-Dalberg family dating back five hundred years.

10. Try to live as a Christian

… in deeds and not just words.

Understand your responsibility to “God and man,” as the Grundgesetz, the postwar Constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany, says in its preamble.

The Ten Commandments make sense to everyone; even for those who are not Jews or Christians, they make sense as ethical teachings. But that does not mean that they are always easy to obey, to live out. The great commandment of Christ, “Love your neighbor as yourself,” is particularly helpful for people as they seek to live happily together.

What we can learn particularly well from Christianity is how to deal with mistakes correctly. I make mistakes; everyone does. We all hurt others sometimes; we all fail to love perfectly, to live in responsible friendship with each other.

The only thing that helps is asking for forgiveness and seeking reconciliation.

When we watch politicians or corporate bosses betray their trust, running from ruin to ruin, most of the time, they refuse to admit mistakes; they refuse to turn around and ask forgiveness. If this happens at all, it often happens long after it should.

And of course in a marriage, asking for and giving forgiveness – reconciliation – is the central tool for finding each other again.

Reconciliation means putting things in order, setting up good patterns for our lives together, ones that will last for a long time. Reconciliation brings things and people back into balance. Reconciliation creates lasting friendships and family bonds. This also applies between peoples.

Sustainable family forests in Wallhausen and Dalberg.

A look ahead

We all feel it: we live in exciting times. We are facing enormous challenges: new media, technological changes, financial crises, climate change, war and problems with domestic security, demographic changes, concerns about the cohesion of society, refugee flows, epidemic diseases, changes in the balance of power globally, renewed fear of nuclear war.

Our time feels fragile. We have to be smart about that. There are no simple solutions. The world situation is complex and interwoven.

I am convinced that right now we need models, good examples. I have presented three good examples from which we can learn sustainability: family, nature, and Jesus Christ.

We can no longer afford to play with ephemeral notions, or to live looking only to ourselves. We have to rely on values that endure: economically, ecologically, and socially. We need long-term thinking – ultimately, eternal thinking.

To me, these ideas are a matter of course, though not because of any merit of mine: they are a gift, given to me by my ancestors.

It would be helpful if the self-evident became common property: these ideas belong to us all, they are the teachings of the world’s wisdom traditions, of all of our ancestors.

Every generation, every century has its own challenges. Every generation asks itself the question: how can we build something that matters – that seeks the common good – something that lasts?

We will be measured by how we solve the question of balance in peace, in prosperity, in the supply of raw materials and the problems of climate change for our children and grandchildren.

It’s about good balance, equilibrium: what the Greeks called sophrosyne. It is important to preserve this for the long term.

To me, living in balance means happiness. I am happy when I am in harmony with myself, with God and with my neighbor.

And when that harmony is broken, that peace which is called shalom – because sometimes it is broken – we must think again, we must seek forgiveness and reconciliation.

I want to close with that, because reconciliation always makes a new beginning. It is what makes the future possible. It is what brings us back into the life that really is life – even if we have been away from it for a very long time.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.