Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Adventures in Americanaland

-

Music, Memory, and Alzheimer’s

-

Why We Make Music

-

Doing Bach Badly

-

Dolly Parton Is Magnificent

-

Go Tell It on the Mountain

-

Reading the Comments

-

In the Aztec Flower Paradise

-

The Strange Love of a Strange God

-

Is Congregational Singing Dead?

-

In Search of Eternity

-

Violas in Sing Sing

-

Hosting a Hootenanny

-

How to Lullaby

-

How to Raise Musical Children

-

How to Make Music Accessible

-

Chanting Psalms in the Dark

-

The Fiery Spirit of Song

-

The Harmony of the World

-

The Tapestry of Sound

-

Let Brotherly Love Remain

-

Take Up Your Cross Daily

-

The Bones of Memory

-

Poem: “Sunrise and Swag”

-

Poem: “Poland, 1985”

-

Church Bells of England

-

Editors’ Picks: “Walk with Me”

-

Editors’ Picks: “Shakeshafte”

-

Editors’ Picks: “The Least of Us”

-

Forum: Letters from Readers

-

Celtic Christianity on Iona

-

The Catherine Project

-

Mercedes Sosa

-

Covering the Cover: Why We Make Music

-

Music and Morals

-

The Death and Life of Christian Hardcore

-

Vallenato Comes Home

Does Political Music Change Anything?

Socially oriented music isn’t propaganda. It can still transform us.

By Daniel Walden

March 9, 2022

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

A choir of men asks: “Officers, why do you have your guns out?” The song begins with three notes on a piano. Two of them form a perfect fifth in the key of G; the third is an intruder, forming a major second with the root and a perfect fourth with the dominant. Something which ought to sound complete is fragmented and reduced. The chord repeats in triplets, extending itself at the end, a fragment holding on to life. Then strings, led by a first violin beginning at G and reaching up to C before it and the other strings join and echo the piano, followed by the voices. Neither the chords nor the subject matter of the piece have found resolution.

The words the choir sings are the last recorded words of Kenneth Chamberlain, a 68-year-old Black man whose LifeAid medical alert necklace went off by mistake while he was at home. When the police came to his door and demanded entry, Chamberlain said that he was all right and asked them to go away. The police refused, insisting for over an hour that they be allowed in. Finally, they forced open Chamberlain’s door and shot him, first with a Taser and then with handguns. He was taken to the hospital, where he died.

Chamberlain is one of seven Black men commemorated in Joel Thompson’s “Seven Last Words of the Unarmed,” a piece originally written for piano, string quartet, and men’s choir (Thompson has since composed a full orchestration, as well as a vocal score for mixed choir). The piece draws on the last words of seven Black men killed while unarmed, either by police or by self-appointed enforcers of the law. Its format draws on the Seven Last Words from the Cross, a genre that has set Jesus’ last words from the four canonical gospels to music since the early sixteenth century. Thompson’s conscious arrangement of the last words of these men in parallel structure with the last words of Christ invites us to see his suffering and death in theirs.

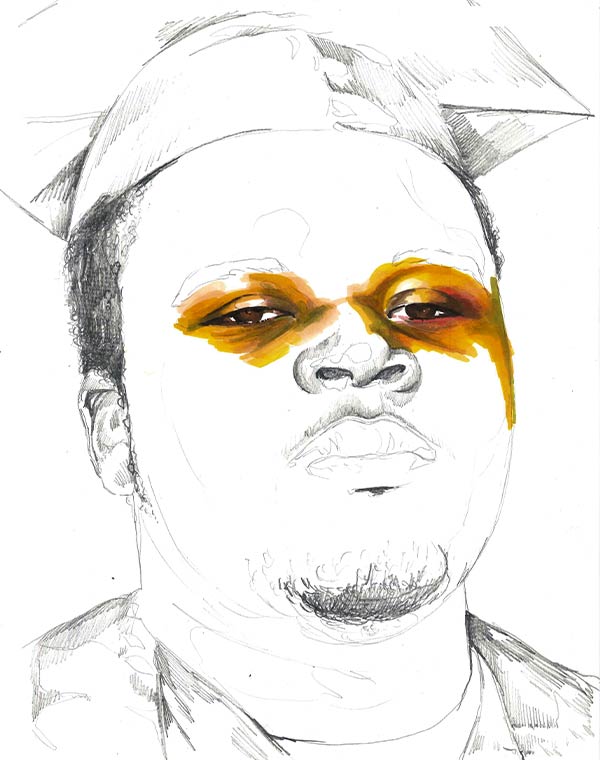

Adrian Brandon, Michael Brown: 18 years old // 18 minutes of color, Stolen Series All images used by permission of the artist

When Eugene Rogers, then associate director of choirs at the University of Michigan, gave the piece its premiere at the fall concert of its Men’s Glee Club in November 2015, it represented a musical elaboration on the first wave of Black Lives Matter protests: both the composition and the protests arose from the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and the state’s subsequent failure to indict officer Darren Wilson. Very few audience members were neutral: most gave a standing ovation, and a visible minority got up and left. The university offered funding for a professional recording and educational materials almost immediately, and more performances were scheduled. Between the masterful composition; consistent, polished performances; and direction by one of the country’s best conductors, it had all the markings of the sort of musical work that is supposed to “change the conversation.”

I sang in the glee club that premiered Thompson’s work. We sang it for South African priest and activist Mpho Tutu at the university’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day symposium, again for the Intercollegiate Men’s Chorus seminar, and again for the premier of the orchestral arrangement the following year. The ride was exhilarating; the piece seemed to get bigger and bigger every time we performed it. But then it was over. When Michigan’s initial performance rights lapsed, nobody took it up for almost a year. After the premiere of the orchestral arrangement, several choirs around the country gave performances, but for the most part the classical music world “wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot pole,” according to Thompson.

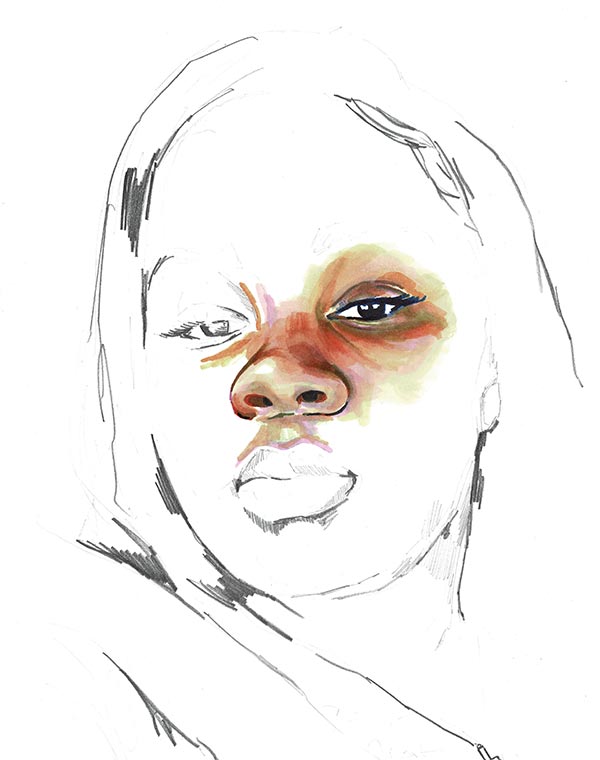

Adrian Brandon, Breonna Taylor: 26 years old // 26 minutes of color, Stolen Series

And then in summer 2020, in the wake of the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, suddenly people were interested in the piece. It was timely and relevant and incisive, excellent things for a piece of art in the abstract, fairly horrifying that it was so relevant six years after its composition. Thompson himself said he was “grateful … but also simultaneously frustrated” with the delayed reception of his work. “I’m hoping that the people who are sharing this piece come to realize how white supremacy has embedded itself into this genre. We need to make substantive structural change to how things are run in classical music.” It’s impossible to overlook the stark contrast between the merits of Thompson’s work – its formal excellence and enthusiastic reception by both professional and popular audiences – and the sheer contingency of its success. It was largely ignored when it challenged the terms of public discussion around police brutality. It became popular only when it was politically expedient for conductors and audiences to signal some token opposition to police violence against Black communities, without any substantive investment in the political action necessary to end it.

What, is the real function of socially challenging music, if its reception depends so much on the narrow moral horizons of the rich and well-connected, those who most need to be challenged and most able to avoid it? Can music ever actually “change the conversation”?

When we pose questions like this about art, we’re usually asking about the experience of the audience: can the experience of a piece of music or an opera or a drama or a painting change how people relate to the world? I would like to be able to answer yes: music has been near the center of my life for many years, and there are works whose performance has never failed to move me to tears, that have become consistent reference points in the process of interrogating and defining who I am. Some conversations, including very important ones about who we think we are, can change in an instant. But when we ask this about music that openly responds to particular social crises, we’re asking whether political conversations can change in substantive ways because of people’s experience of a musical work. I have found that they don’t generally seem to, at least in any way that we can measure.

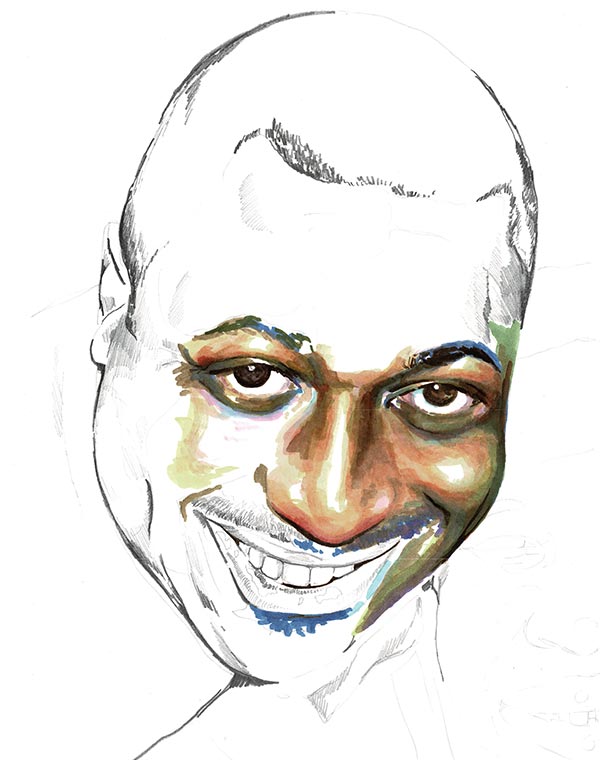

Adrian Brandon, Eric Garner: 43 years old // 43 minutes of color, Stolen Series

This might sound unfair to politically oriented artists, but I don’t think it’s a deficiency in their practice. I have yet to meet an artist with a politically or socially-facing practice who believes that a single work could, on its own, alter the way a community discusses social and political questions. Practicing artists, if they are not delusional, regularly face too much indifference, puzzlement, and hostility from audiences to have so high an estimation of their work’s reach and impact. Why, then, do we continue to speak as though a piece of music will have this sort of impact? The answer is uncomfortable, because it seems to me that we actually don’t expect music in general, or any performing art, to effect political conversion. It’s not part of our matrix for evaluating music, whether we’re thinking about awards for academic compositions like the Pulitzer Prize, or those for commercial music like the Grammys.

There is, in fact, something sinister in the expectation that art is only valuable if it “changes the conversation,” especially when it is predicated upon the pain and loss experienced by minority communities. Such an expectation sets up a perverse chain of reasoning which predicates the worth and importance of Black social art on the ongoing suffering of Black people. “If people hear this piece,” we think, “something in them will open up to this pain and they will have to act.” I am reminded of the resurgence of spoken-word poetry in the 1990s and the pressure on poets to perform suffering in the name of claiming authenticity. In a 2005 LA Times article, poet Sista Queen observed, “We’re the only genre of art that’s supposed to be broke and happy about it … We’re supposed to be sitting on a curb writing poetry on toilet paper.” The growth of a White audience for spoken word did little to improve the political and economic situation of Black Americans, or indeed of very many working poets. The concert hall, it seems, is not always a space that is especially conducive to political epiphanies.

I am convinced that art does educate, but as often as not it is the artist who is changed rather than an audience. The practice of art demands transformation; it will come as no surprise that I think preparing and performing Thompson’s work changed me.

The experience of singing “Seven Last Words” could not have swept us all up as much as it did without the very deliberate educational program that Rogers undertook with the choir. The goal of any performance is a certain kind of authenticity: a performer needs to embody a work, to let the work take center stage. For that reason, Rogers’s preparation combined detailed attention to the lives of the seven men named in the piece with a universalizing appeal to grief at the senseless loss of their lives. Their particularity was essential: seven men who had lived and died far away from Ann Arbor became our close companions during months of rehearsal. Such attention allowed the memorial dimensions of Thompson’s work to come through and allowed us to understand our own role not only in raising awareness of injustice, but in honoring their lost lives. For singers who, for the most part, had never grappled with the dangers of police and vigilante violence that constantly threaten Black people in the U.S., even such distant grief was instructive. Our knowledge of police violence changed from a list of numbers, to a ledger of names. For all its reputation as an abstract art form, music led us to the particular.

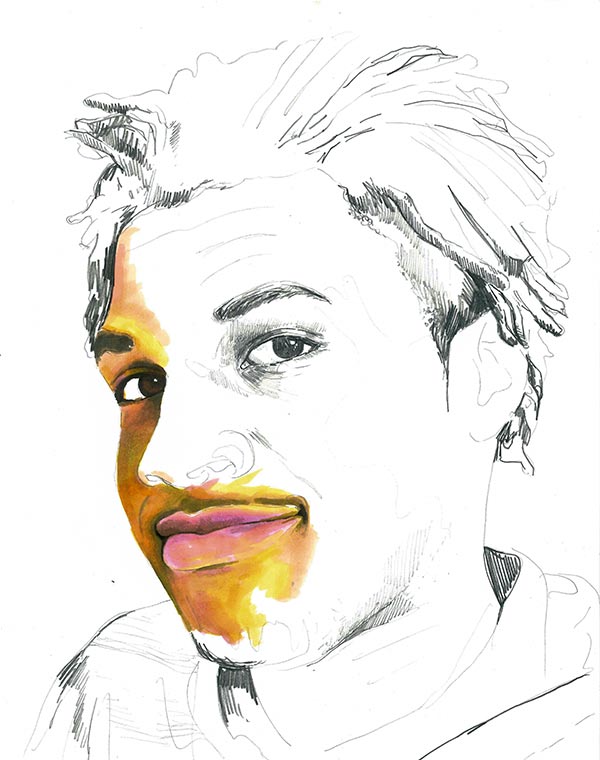

Adrian Brandon, John Crawford III: 22 years old // 22 minutes of color, Stolen Series

We needed this time not only to live with the subject matter but to understand the piece as music. Any socially-facing art risks being reduced to a “message,” and the performance reduced to conveying that “message” to an audience. But composers are not only writing a message – they are writing music, sometimes with text and sometimes not. Only by coming to understand a piece as music can we open ourselves to the expansion and transformation that comes from deep engagement with music as music, not propaganda. What we learn from this attention is the humanity of other people. Sound is natural; music is human. To understand music is to come to terms with the intention and particularity that led a specific person see to it that pitches and rhythms were arranged just so. Encountering humanity means, paradoxically, reckoning with particular intentions and particular lives – the intentions of one composer; the lives, deaths, and memories of seven unique men. This humanity is definitive of music – basic to it – but precisely because it is so fundamental, it demands serious attention for it to become apparent.

I don’t want to discount the instantaneous apprehension and transformation that a magnificent performance can sometimes grant. But I understand such moments as the direct operation of grace, as a breaking-through of humanity through divinity, happening not because of our receptivity but despite our lack of it. We are grateful for such moments, but we cannot depend on them. What we can do is practice the attention and the empathy of music, the opening-up of ourselves to the view of another human being, the willingness to be moved.

Such a practice can attune us not only to the contours of notes, rhythms, and dynamics but to the contours of the lives of those around us: they, too, reward our disciplined attention. The lesson we learn from coming to know another person – their struggles and triumphs, their gifts and their needs – can be a hard one because of the burden it lays on us once we have grasped it adequately. It demands radical things: the cessation of all violence, the provision of every need, the forgiveness of sins. The potential for art to transform us is precisely its potential to teach this, and to show us that the humanity of others – that is, their life with us and among us, in all its messy details and its frustrations and its blessed imperfection – is the indispensable foundation of our own humanity. The practice of artistry can help attune us to that reality. God tells us that it is not good for the human being to be alone; music and the other arts can teach us, if we care to learn, that we are not.

Our task is to begin living as if this is true.

Listen to the piece:

Daniel Walden is a writer and classicist. He spends his time thinking about Homeric philology, Catholic socialism, musical theatre, and the Michigan Wolverines.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.