Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Vallenato Comes Home

-

Does Political Music Change Anything?

-

Adventures in Americanaland

-

Music, Memory, and Alzheimer’s

-

Why We Make Music

-

Doing Bach Badly

-

Dolly Parton Is Magnificent

-

Go Tell It on the Mountain

-

Reading the Comments

-

In the Aztec Flower Paradise

-

The Strange Love of a Strange God

-

Is Congregational Singing Dead?

-

In Search of Eternity

-

Violas in Sing Sing

-

Hosting a Hootenanny

-

How to Lullaby

-

How to Raise Musical Children

-

How to Make Music Accessible

-

Chanting Psalms in the Dark

-

The Fiery Spirit of Song

-

The Harmony of the World

-

The Tapestry of Sound

-

Let Brotherly Love Remain

-

Take Up Your Cross Daily

-

The Bones of Memory

-

Poem: “Sunrise and Swag”

-

Poem: “Poland, 1985”

-

Church Bells of England

-

Editors’ Picks: “Walk with Me”

-

Editors’ Picks: “Shakeshafte”

-

Editors’ Picks: “The Least of Us”

-

Forum: Letters from Readers

-

Celtic Christianity on Iona

-

The Catherine Project

-

Mercedes Sosa

-

Covering the Cover: Why We Make Music

-

Music and Morals

The Death and Life of Christian Hardcore

The Christian underground came undone as it rocketed to relevance.

By Joseph M. Keegin

February 25, 2022

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Bushnell is a sleepy rail town of under 3,000 on the western edge of central Illinois, less than an hour’s drive from the Iowa border. An unassuming cluster of brick storefronts, sheet metal factories, and cylindrical granaries along the train tracks, it is enveloped on all sides by an ocean of cornfields, endless in all directions. A potato chip factory and a plant that makes hammers constitute its major industry; it also appears to be the ancestral home of rolled oats. But for twenty years it served as the home of Cornerstone Festival, the largest Christian music and arts festival in the entire world. Founded by Jesus People USA, a Chicago-based Christian commune affiliated with the post-Lutheran Evangelical Covenant Church, Cornerstone was launched in 1984 as “the Woodstock of the Jesus freaks” – initially held at a fairground in the Chicago suburb of Grayslake, the festival moved to a former farm in Bushnell in 1991. Every summer from then until 2012, some 25,000 to 30,000 people made the pilgrimage to rural Illinois to camp in a field, get rowdy, and worship God.

The scale of the operation aside, one thing made Cornerstone stand out amid countless other Christian music festivals. Alongside artists who made up the “mainstream” of Christian contemporary music (or CCM) – performers like Amy Grant, Jars of Clay, DC Talk – there were countless names that nobody who got their bearings from Christian radio would have recognized. And if you happened to wander ignorant into one of their sets, you wouldn’t find the placid, hand-waving praise-music audience you anticipated. Instead, you’d see dozens – if not hundreds – of youngsters with mohawks and patch-covered jackets slamming into each other to music of a brutality and volume you could not have imagined. You would have stumbled, as many did over the years, into the vibrant and intense underground of Christian hardcore.

In the early ’90s, an explicitly Christian scene began to grow inside the broader American music underground. In cities that incubated the punk rock of the ’70s and ’80s – places like Los Angeles, San Diego, and Philadelphia – “spirit-filled hardcore” bands with unequivocally religious lyrics began playing shows, releasing demos and records, and building an enthusiastic audience. But by the turn of the millennium, postindustrial flyover cities like Little Rock, Memphis, Birmingham, and various towns in Florida became the Christian underground’s most fertile seedbeds.

In all waves, however, it was a thoroughly Evangelical affair, drawing from the ranks of Baptists, Pentecostals, and various nondenominational movements that rose to prominence in the ’80s and ’90s. It was a kind of gospel music of the disaffected youth at the End of History, one that sought to baptize punk rock and use it for purposes other than nihilistic rage. But it’s a misunderstanding to think of the Christian scene as simply a religious version of a fundamentally secular style of music. Many Christian bands were pivotal in staking out certain hardcore and metal subgenres: Eso-Charis and Training for Utopia count among the earliest metalcore bands; Focal Point and No Innocent Victim were “tough-guy” hardcore contemporaries of future Grammy nominees Hatebreed; Strongarm and Hopesfall were the earliest pioneers of a heavy-but-melodic sound that would later become fully mainstream. In some of these micro-scenes, God-fearing bands outnumbered the heathen.

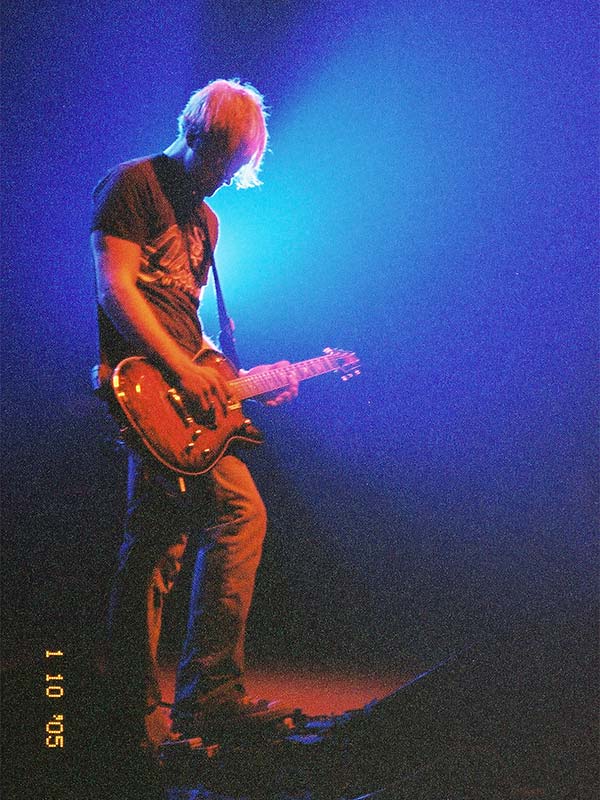

Underoath performing at Northern Lights Music Festival, 2009 Photograph by Jake Przespo

In the early ’90s, however, when “secular” punk rock and hardcore was shaped according to the sentiments of groups like the Dead Kennedys (“all religions make me sick / all religions make me wanna throw up”), Crass (“He hangs upon his cross in self-righteous judgment / hangs in crucified delight, nailed to the extend of His vision”), and Minor Threat (“you picked up a Bible and now you’re gone / you call it religion, you’re full of shit”), Christian heavy music was forced to operate in an entirely separate, parallel universe. Christian bands were often unwelcome, excluded from the bars and punk venues similar-sounding “secular” bands would play, so many booked church basements as music venues. (The first hardcore show I ever attended was in a church basement in Mississippi.) But in many ways this exclusion became an advantage. Pastors saw a great opportunity for youth engagement; parents who hesitated to drop their teenagers off at a seedy club or punk house were thrilled to see their kids spending more time in a church; middle-American teenagers who might otherwise while away the hours pipe-bombing mailboxes or developing drug addictions found a place for positivity and a community oriented toward the highest good.

The difficulty for the Christian underground was finding someone to record and release their music. Punk-rock record labels simply did not want to put their names on albums that spoke openly about religious faith; the existing Christian music industry had no place for caustic, distorted, energetic rock ‘n’ roll. So in the early ’90s, a handful of small labels sprang up around the country: on the West Coast, Rescue, Tooth & Nail, Facedown, Bettie Rocket, 5 Minute Walk, and Screaming Giant Records launched in California, and Portland became home to Boot to Head; out East, there were Cleveland’s Steadfast, Philadelphia’s Burnt Toast, and Takehold Records in Birmingham. Most began in bedrooms, basements, and apartments; many lived and died without ever having an office. Distribution for most labels was limited to mail order and a smattering of friendly independent record stores around the country.

But around the turn of the century, the veil of obscurity over the scene began to part. By the mid ’90s Tooth & Nail had established a near-monopoly on the Christian music underground, becoming the largest independent record label in the Pacific Northwest. In 1997, owner Brandon Ebel founded the subsidiary Solid State Records to focus more aggressively on punk and hardcore music, and at the same time brokered a major distribution deal which would get their bands’ albums into far more music stores than ever before. Christian heavy music suddenly had the imprimatur of institutional legitimacy and respectability. Christian bands began to appear on “secular” showbills and festival lineups; the Tooth & Nail pop punk bands MxPx, Puller, and The Supertones ran videos and played live performances on MTV.

In 2000, Takehold Records founder Chad Johnson launched Furnace Fest, a weekend-long, one-stage hardcore festival at the decommissioned Birmingham iron foundry Sloss Furnaces. The festival was one of the first opportunities for Christian bands – heretofore confined largely to Cornerstone – to share a festival stage with bands from the broader secular music underground, and for fans from both scenes to come together at a scale much larger than the usual clubs and backrooms afforded. It was a resounding success, bringing out thousands. And over the next three years, Furnace Fest served as one of the country’s most energetic underground music festivals, affording a totally new level of Christian-secular cross-pollination.

It proved a success for Johnson personally, as well. Takehold had been ailing since its founding, the popularity of the label far outpacing its resources. Certain of its bands were hungry for better representation and marketing; some had been poached by the rapidly growing Tooth & Nail. In 2002, Tooth & Nail made an offer to buy Johnson’s label and take over the Takehold catalog. He accepted, trading his executive position for a job in Tooth & Nail’s marketing wing. Most of Takehold’s bands would be ported over to heavy music subsidiary Solid State, and from there Christian hardcore would take over the world: former Takehold band Underoath would become Christian hardcore’s first breakout act; four years later, they’d bring Tooth & Nail its first gold record.

Ben Kasica performing at a Skillet concert, 2005 Photograph by Wewillprosper

Christian hardcore underwent a complete metamorphosis in the 2000s. Around the time of the Takehold buyout, the colossal music conglomerate EMI caught a glimpse of possible profits and began buying shares of Tooth & Nail. The label started in an apartment living room had won the attention – and the capital – of one of the largest music corporations in the world. By the mid-2000s, Christian hardcore had become ubiquitous: Solid State artists could be found on MTV, on the radio, in Target. Many bands, upon their first encounter with mainstream relevance, began to sideline references to faith in their lyrics, disavow religion in interviews: “Christian hardcore” had proven a convenient label for building an early audience, but every butterfly must shed its chrysalis. (And every snake its skin.) There proved an inverse relationship between popularity and piety. “We’re Christians in a band,” many would say in interviews, “not a Christian band.”

My own brother, Jon Keegin, played in Few Left Standing, a band that was signed to Takehold in the early 2000s. By the time of the Tooth & Nail buyout, they had become fierce critics of what they were seeing. “All of this stuff began when a bunch of working-class kids like us started bands in the service of ministry,” he told me. “But when it got big, the scene flooded with kids from the suburbs who used the appearance of ministry in service to their band. The fame took over.” A song on Few Left Standing’s second and last album rails against this tendency:

Forget the cause, image is where it's at

Be all you can be if it suits your purpose

Using Him as a cover and taking up the latest fad

It's all a religious fashion show

Trends come and go

But Christ will always remain the same

Frustration with the direction of the scene and budding domestic obligations – marriage, children, the need for stable careers – led to the band’s breakup in 2002. They wouldn’t be the only ones to make an exit: as the next generation of bands bloomed, many had a hard time adjusting to the rigorous touring and recording schedules demanded by their labels, their new relevance producing an increased concern for the bottom line.

As Christian hardcore rocketed to relevance it laid the groundwork for its own undoing. The tight-knit, church-basement scene evaporated as more and more bands entered a touring market of big festivals and high guarantees. In 2010, EMI established full ownership of Tooth & Nail, ending its career as an independent label and making it yet one more investment of a multinational music conglomerate. (Tooth & Nail bought its name back – and with it, the ability to operate as an independent label – in 2013, but its back catalogue remains in the hands of former EMI subsidiary Capitol Records.) Cornerstone gradually dwindled, finally calling it quits in 2012. And then in 2013, Tim Lambesis, singer of the band As I Lay Dying – arguably the most successful Christian hardcore band in America at the turn of the millennium – was arrested for attempting to hire a hitman to assassinate his estranged wife, proving in grand form the suspicions of detractors: that the Christians, despite their sanctimony, were hypocrites. The scandal was the last straw for the beleaguered scene. The few bands that drifted to the top continued to enjoy success, but as exceptions that proved the rule: hardcore had become mainstream, but Christian hardcore was over.

In November 2019, Chad Johnson and a handful of partners announced that Furnace Fest would return to Birmingham the following September to celebrate the festival’s twentieth anniversary. The proposed lineup was peppered with familiar names as well as with a surprising number of artists from a new generation. The pandemic ultimately delayed the event until 2021. But when last September came around, several thousand people decamped for Birmingham and crowded into Sloss Furnaces to bring hardcore back to life.

My brother’s band was one of several to brush off the dust of a decade and give it one last go, and naturally I tagged along. I’d prepared for a weekend walk through a museum: a Christian hardcore exhibit featuring old punks gone to seed, bands far past their peak, and everyone trying to crank out one last show for their aging, nostalgic fans, everyone’s longing sated but not without a lingering sense of melancholy. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The festival was a lively, highly convivial affair, the attendees from a wide range of ages; it was hard to imagine that many of the bands hadn’t performed live for over a decade. And despite its happening nearly a decade after the peak of Christian hardcore, after so many bands and band members abandoned their faith along the way, there was no shortage of references to God.

Among the most anticipated acts of the festival was former Solid State band Beloved, which disbanded in 2005 after releasing a few well-loved albums and playing some early Furnace Fests. Before they began, Johnson took the opportunity to say a few words to the crowd. “You’ve given me so many compliments all weekend,” he told the audience, “but the one thing you’ve forgotten is that this has so little to do with me and so much to do with you.” The audience howled. But then something happened that felt like an echo of the past. “Our hope has always been that we can rise above all of this,” Johnson implored, “so I’m going to give you a little piece of my heart.” And then he began to pray. “Father God I pray that you would bless my friends, bless my family, bless every single individual here … help us, lift our burdens, lift our hurts, lift our anger, lift our hatred, lift anything that keeps us from love. Overwhelm us with love. In Jesus’ name, Amen.”

And the crowd roared.

Special thanks to Jon Keegin and Rob Froese for helping with this piece.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

colleen d

Thanks for the article - I appreciate your take on this

Calla

Thank you for this article! I'm an 80s baby who grew up on Tooth and Nail. I will be attending mewithoutYou's farewell tour in August for my one last taste of Christian Hardcore. May the nostalgia live on!