Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Jakob Hutter

-

The Bruderhof and the State

-

Saint Patrick

-

Reading Romans 13 Under Fascism

-

Holding Our Own

-

Living with Strangers

-

Tolstoy’s Case Against Humane War

-

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Conscientious Objector”

-

Oscar Romero

-

The Martyr in Street Clothes

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 24

-

Van Gogh Comics

-

Boys Aren’t the Problem

-

The Woman Who Carried Me

-

Samuel Ruiz García

-

Christian Nonviolence and Church History

-

American Muslims: Race, Faith, and Political Allegiance

-

Ministers and Magistrates

-

Pick the Right Politics

-

Editor’s Postscript: Notes from the Lockdown

-

Readers Respond: Issue 24

-

Family and Friends: Issue 24

-

What Goes Up

-

The Politics of the Gospel

-

What Are Prophets For

-

Bishop Ambrose

The Anabaptist Vision of Politics

The church, not the state, gives history its meaning.

By John D. Roth

March 25, 2020

Available languages: español

This article is part of the Anabaptism and Politics series.

On april 27, 2003, the citizens of Paraguay elected a new president. Paraguay is such a small country – its population was only 5.5 million at the time – that the story barely garnered a mention by the major US networks. Yet for Mennonites in Paraguay, the election of Nicanor Duarte Frutos that spring was a momentous event. Although the newly elected president himself was Catholic, along with 90 percent of the country, Duarte’s wife, Gloria, was an active member of the Raíces Mennonite church, a large Spanish-speaking congregation in the capital city of Asunción. Moreover, for several years, Duarte himself, along with the couple’s five children, regularly attended the church.

In the weeks that followed the election, the Mennonite connection to Paraguayan politics became even more visible. By the summer of 2003, for example, Duarte had persuaded four Mennonites to serve in cabinet-level positions in his government – proof, he claimed, of his seriousness about cracking down on government corruption. In the fall of 2003, Duarte resisted pressure from US president George W. Bush to send troops and military aid to Iraq, citing his Christian convictions and the pacifist witness of his wife’s congregation. In the meantime, he continued to attend worship services at the Raíces congregation, now accompanied by a retinue of armed bodyguards.

Duarte’s public association with the Mennonites of Paraguay evoked a fierce debate among the country’s Catholic elites, who took it for granted that Paraguay was a Catholic country. But it also triggered an animated discussion among Mennonites there about the relationship between church and state, a discussion deeply embedded in the nearly five-hundred-year-old Anabaptist-Mennonite tradition.

Anabaptist Origins

The Anabaptist movement – which gave rise to groups like the Hutterites, Mennonites, and Amish – emerged in the sixteenth century within the tumultuous context of the Reformation. When Luther appealed to the authority of “scripture alone” (sola scriptura) and invited ordinary people to read the Bible in the vernacular, he assumed that all earnest Christians would arrive at the same conclusions as he did. For Luther, of course, the great insight revealed by Scripture was the distinction between gospel and law, and the conviction that humans are saved by grace alone. But others discovered in the same biblical texts – especially in the teachings of Jesus – a blueprint for social transformation. During the Peasants’ War of 1525, thousands of peasants and artisans in southern Germany, appealing to Luther’s principle of sola scriptura, rallied around the “Twelve Articles.” They demanded the right to elect their own pastors; freedom of movement; fair treatment in taxes, tithes, rents, and corvée labor; and the right to hunt and fish or gather wood. Although their concerns sound tame today, in the context of the sixteenth century the Twelve Articles challenged fundamental political and economic assumptions of feudal society. Perhaps their most revolutionary aspect was their explicit appeal to the Christian conscience. “If one or several of the articles mentioned here are not in accordance with the word of God,” the writers insisted, “we shall withdraw them if it is explained to us on the basis of the Scripture.”

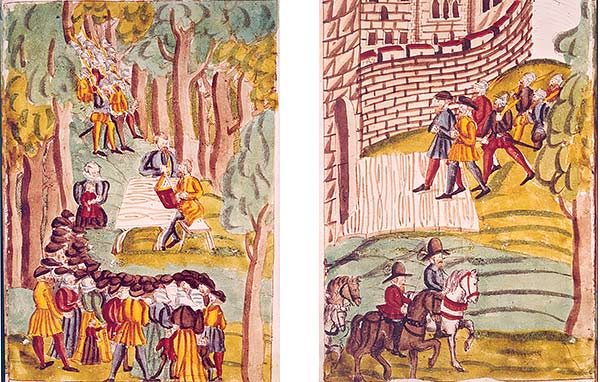

Engraving by Jan Luiken showing the 1637 arrest of Anabaptists in Zurich, Switzerland (public domain)

The Peasants’ War marked a decisive moment in Christian political theory. Under pressure from his prince to restore social order – and in the interest of preserving his reforms – Luther sided firmly with the feudal lords. In May he published “Against the Robbing, Murderous Hordes of Peasants,” an incendiary tract that called on the princes of Germany to spare no blood in crushing the uprising. Shortly thereafter, at the battle of Frankenhausen, the peasants were brutally crushed. Going forward, Luther further expanded his conservative political theology, consistently defending the princes and secular government as an extension of God’s authority in the ordering of creation.

The Anabaptist movement emerged in 1525 precisely at the intersection between the violent revolutionary vision of the Peasants’ War and Luther’s defense of a state church, overseen by a prince ordained by God to preserve social order.

Like all the Reformers, the early leaders of the Anabaptist movement in Switzerland and south Germany insisted that Christian faith and life should be shaped by Scripture alone. A Christian’s first allegiance, they argued, is to Christ and his teachings, not to the pope or – and here they broke with Luther – to a feudal lord or prince. On the basis of Scripture, the Anabaptists (“rebaptizers”) rejected infant baptism. Following Jesus, they believed, required a voluntary decision – Peter, James, and John were not forced to leave their nets when Jesus invited them to become “fishers of men.” At stake in this decision were fundamental questions of identity and allegiance. In the emerging Anabaptist understanding, baptism marked a believer’s public acceptance of God’s gracious gift of forgiveness, but this same act also signaled a commitment to become part of a voluntary gathering of Christ-followers whose lives were transformed by the Holy Spirit. Baptism was about metanoia – repentance, turning around – that found expression in daily discipleship in the context of a Christian community. Through the Holy Spirit, followers of Jesus were part of a “new creation,” a new form of politics with tangible social, economic, and political consequences.

Followers of Jesus were part of a “new creation”: a new form of politics with tangible social, economic, and political consequences.

Thus, for example, the Anabaptists took seriously Christ’s admonition in the Sermon on the Mount against swearing oaths (Matt. 5:33-37). Feudal oaths were the glue that held medieval society together. In a context where the political order was always precarious, oaths ensured that civil obligations would be honored by invoking God’s punishment on those who violated their promises. Yet the Anabaptists refused, insisting that Christians always spoke the truth – not just when they were under oath – and that their consciences could not be bound by political promises.

They also assumed that following Jesus entailed a radically new understanding of private property. Some Anabaptist groups, like the Hutterites, shared all possessions in common, in keeping with the example of the apostolic church in Acts 2 and 4. Other groups practiced radical mutual aid, with the understanding that each member would share freely as the need arose. Virtually all Anabaptists rejected the practice of “merchandising” – buying low, with the goal of selling high – and they were ready to forfeit their land and homes in service to Christ’s call.

Perhaps the most politically provocative teaching of the Anabaptists was their renunciation of lethal force. Already in the fall of 1524, as tensions among the peasants were escalating, Conrad Grebel, a leader among the Anabaptist dissenters in Zurich, challenged Thomas Müntzer and his revolutionary peasant army to reject the sword: “The gospel and its adherents,” Grebel wrote, “are not to be protected by the sword, nor should they [protect] themselves…. True believing Christians are sheep among wolves, sheep for the slaughter…. They use neither worldly sword nor war, since killing has ceased with them entirely.” Although Anabaptist groups disagreed over whether or not they could serve as guards in the town watch, or pay taxes that funded wars, or accept protection from armed soldiers, they were nearly unanimous in their conviction that Christians could not willingly take the life of another human being.

Sixteenth-century paintings show an illicit Anabaptist meeting followed by the arrest of two Anabaptist preachers From a collection in the Central Library of Zurich, obtained from Heinold Fast

In the context of European Christendom these practices were profoundly unsettling. Unlike the inhabitants of a monastery – the closest parallel to their vision – the Anabaptists understood these teachings of Jesus to be a mandate for all Christians. The Christian community they envisioned would be a concrete sociopolitical alternative to the feudal and religious structures of their day, a way of life intended for everyone who professed the name of Christ.

The authorities, however, regarded their actions as a threatening disruption to civic order. With memories of the Peasants’ War still fresh in mind, Catholic and Protestant princes joined efforts to suppress the movement. In the course of the sixteenth century, authorities executed between two and three thousand Anabaptists, with thousands more imprisoned, tortured, branded, fined, or forced into exile. The experience helped to confirm an Anabaptist view of the state as inherently violent, defined primarily by its role in wielding the sword.

Separation – and Engagement

In the face of intense persecution, Anabaptist political theology tended to emerge contextually rather than in systematic treatises like those written by Luther or Calvin. Balthasar Hubmaier, for example, still thinking in terms of a communal reformation, envisioned the possibility of a Christian magistrate. More typical was the formulation expressed in one of the first formal statements of early Anabaptist beliefs called the Brotherly Union (or Schleitheim Confession) of 1527. In that statement, Anabaptists in Switzerland and south Germany recognized the sword as “an ordering of God,” wielded by secular rulers in a fallen world to punish the wicked and protect the good. But where Luther argued that Christians could perform this public office in good conscience, even as they were held to the higher commands of Christ in their private lives, the Anabaptists insisted that the sword was “outside the perfection of Christ.” The statement continued: “The worldly are armed with steel and iron, but Christians are armed… with truth, righteousness, peace, faith, salvation, and with the Word of God.” Within the perfection of Christ “only the ban is used for admonition… simply the warning and the command to sin no more.”

Title page of the Schleitheim Confession, an early Anabaptist statement of faith from 1527 (public domain)

Later Anabaptists sought to assure authorities that they were not seeking open revolution, citing scriptures that called on Christians to honor authorities and to pray for government leaders. At the same time, however, they generally refused to participate as magistrates, judges, soldiers, prison guards, or police. And they continued to live in disciplined communities whose practices were often visibly distinct from those of the surrounding society. Hutterites, for example, continued to challenge assumptions about private property by sharing their possessions. Until recently, most Amish and Mennonites did not vote, say the pledge of allegiance, or join the military. The primary focus of God’s redeeming work in the world, they believed, was the lived example of the Christian community as an alternative sociopolitical reality. The state – rather like a utility company – served a useful public purpose, but for the Christian it had no divine status and was therefore not worthy of absolute allegiance.

At its best, this understanding embodied the New Testament metaphors of the church as the “light of the world” or as a “city set on a hill.” The first task of the Christian community is to bear witness to the radical teachings of Jesus in its own communal practices and in the compassion it extends outward to the neighbor and stranger. This was not quietist or apolitical withdrawal. The church is called to feed the hungry, care for the poor, bind the wounds of the oppressed, and to weep with those who weep. In so doing, it bears witness to God’s intention for the whole world, including the state. But Christians should also not be seduced by arguments for effectiveness, by worldly forms of power, or by the illusion that darkness can be overcome with darkness.

At its worst, this dualistic view of a sharp separation between church and state became a complacent, even arrogant, strategy of self-preservation. In exchange for toleration, descendants of the Anabaptists made themselves economically useful to the state and politically quiescent. With the exception of the Bruderhof, few Anabaptists in Germany spoke out against the rise of Hitler and National Socialism. And the Mennonites who found refuge from oppressive governments in the Paraguayan Chaco in the 1930s and 1940s remained silent during the lengthy dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner, who publicly extolled their economic contributions even as he ruled with an iron fist from 1954 to 1989, torturing and executing hundreds of political dissidents.

New Understandings of Political Witness

During the past fifty years, the political theology of several Anabaptist groups has undergone a significant shift as a result of new social contexts as well as new theological insights. In North America, the experience of thousands of young men in Civilian Public Service (CPS) camps during World War II, and then in overseas relief assignments in the decades following the war, opened many Mennonites to a new sense of Christian responsibility for the needs of the world, and to the structural (i.e., “political”) nature of oppression. CPS volunteers who witnessed the inhumane treatment of inmates in mental health institutions, for example, became pioneers in the struggle to reform mental healthcare, including public relations campaigns and political lobbying for legislative changes. In the 1960s, the civil rights movement convicted the consciences of many Anabaptists to challenge the legal structures that supported racism. At the same time, some Anabaptists, deeply troubled by the war in Vietnam, began to engage in war-tax resistance and participate in antiwar demonstrations. Others pursued legislative solutions in the struggle against poverty.

Here the story of the Mennonites in Paraguay is particularly instructive. In 1989 Stroessner was forced out of power in a bloodless coup that ultimately led to the formation of a liberal democratic state, based on a constitution, the rule of law, and regular elections. Suddenly, Mennonites, who had become a major economic force in Paraguay, were invited to help shape the future of the country, including the formulation of a new Paraguayan constitution. Should they join with other groups to advocate for religious freedom? For the separation of church and state? For a constitutional provision for conscientious objection? In the end, key Mennonite leaders quietly participated in the process.

The first task of the Christian community is to bear witness to the radical teachings of Jesus in its own practices and in the compassion it extends to the stranger.

Other forms of political engagement also emerged in the 1990s, when a growing number of Paraguayan Mennonites moved from the relative isolation of their colonies in the Chaco to the capital city of Asunción in pursuit of higher education; export markets for their expanding dairy, grain, and beef enterprises; or labor for their entrepreneurial industries. There they directed their newfound wealth to fund a host of innovative social ministries. Mennonites started a Christian radio and television station; they established addiction treatment centers and alternatives to the state mental health facility; they created job-training programs and schools in low-income neighborhoods; and they helped to transform portions of the country’s notorious Tacumbú prison into an internationally recognized model of humane treatment and rehabilitation – all under a commitment to “seek the welfare of the city” (Jer. 29:7).

Nicanor Duarte Frutos with his wife, María Gloria Penayo, on the day of his election (public domain)

The presidential campaign of Nicanor Duarte Frutos in 2003 confronted Mennonites with yet another form of potential political witness. Although Duarte was a member of Stroessner’s Colorado Party, he was elected on a reform platform committed to rooting out governmental corruption. As part of that effort, Duarte asked several Mennonites to oversee key areas of his government, including the offices of internal revenue, commerce, health services, and international economic relations. Initially, each reportedly declined the invitation, arguing that Mennonites were “non-political.” Yet Duarte persisted. His most convincing argument asked them to imagine trying to play soccer on a field littered with broken bottles, metal scraps, and construction debris. For fifty years, he claimed, that’s what politics in Paraguay had been like – it was impossible to participate without getting injured. “We’re not asking you to be players in the field,” Duarte argued. “But up until now, you’ve just been sitting in the stands, watching from a safe distance. What I’m asking is for you to get out of your seat and to come down and help me clean up the field so that we can play in a safe, decent, and fair way.” The argument was persuasive.

Before they agreed to serve, however, church leaders gathered to formulate several principles of shared understanding. First, the focus of their service was to remain on the well-being of the Paraguayan people as a whole, not on the interests of Mennonites. Each of the cabinet appointees had an “accountability group” of church members who would encourage them to resign if they were ever forced to make choices that would compromise their ethics. They agreed that they would not become “professional” politicians, dependent on the job for their livelihood or identity. And, finally, they would not claim affiliation with any political party – a remarkable concession by Duarte since cabinet-level positions were part of the spoils to be distributed as favors to party loyalists.

In the short term, the experience was a success. Tax revenues rapidly increased; Paraguay successfully negotiated new terms with the IMF and World Bank regarding its debts; the quality of healthcare improved; and journalists noted a marked shift toward greater transparency in government finances.

From a longer perspective, however, assessments of these new forms of political witness were more ambiguous. Some of the Mennonite cabinet officials received death threats and found it necessary to travel with armed guards, in apparent contradiction of their nonviolent convictions; most resigned within the first two or three years, frustrated by the constraints of their offices. Duarte himself came under suspicion for attempting to change the constitution to permit longer presidential terms.

The realities of electoral politics also raised new and complicated questions. Within the newly created province of Boquerón, Mennonites living in long-established colonies formed the overwhelming majority of potential voters. Boquerón had its own elected governor who oversaw a police force and judicial system. Should Mennonites run for the office of governor? Should they be represented in the Paraguayan Senate and Chamber of Deputies? Should they engage in party politics? Form their own “Mennonite” party? Seek office only as “independents”? The Mennonite colonies, run as cooperatives, had traditionally placed a high value on collective decision-making. Now, new strains appeared in the community as candidates for various political offices began to court specific constituencies, sometimes pitting the interests of wealthy Mennonite landowners against landless Mennonites or indigenous day laborers.

By the first decade of the twenty-first century, US Mennonites were experiencing similar dilemmas, especially as conservative groups began to also “seek the welfare of the city” by aligning with the religious right and becoming politically active around issues related to marriage, sexuality, and abortion. Sadly, the political witness of many Mennonites in the United States today, as in Paraguay, basically aligns with the partisan divisions of the broader culture, with members on both sides of entrenched political divides.

Looking to the Future

So what have we learned from five hundred years of Anabaptist understandings of church and state? There are a few lessons worth noting.

First, contemporary Anabaptist political theology, particularly since World War II, has challenged the dualistic tendencies of its own tradition by affirming more clearly that nonviolent love is the will of God for everyone – Christians and non-Christians alike, in all settings. This conviction challenges the hypocrisy of some traditionalist Anabaptist-Mennonite groups who cheer on the US military and support capital punishment while refusing to participate in military service. The Christian witness to the state must always speak clearly in support of loving nonviolence; Christians should never acquiesce to violence. But pacifist Christians also recognize that there are people and structures who do not yet acknowledge the lordship of Christ. In those circumstances, Christians should vigorously advocate for solutions that point in the direction of nonviolent love, even if the solutions fall short of the ideal. Thus, for example, Christian pacifists may be resolutely opposed to war and still actively support the Military Code of Conduct, which forbids such things as torture and extrajudicial killing; they can publicly denounce the nation’s decision to go to war, while also expecting it to abide by the Just War principles it has agreed to follow. Christians who believe in the sanctity of life may have strong views against abortion, while still advocating for legislative measures that make contraception widely available or provide economic support to young teens struggling with difficult life choices. These forms of political witness, however, all emerge out of an explicit commitment to the radical claims of the gospel. And while they may include alliances with other groups, they almost certainly will not align neatly with the standard partisan divides of the national political culture.

Christian pacifists may be resolutely opposed to war and still support the Military Code of Conduct.

Second, Anabaptist Christians engaged in political activism should cultivate spiritual disciplines that remind them that their first and primary citizenship is in the Body of Christ. Before Jesus began his public, intensely political ministry, he spent forty days fasting and praying in the wilderness, confronting the temptations associated with power.

The most powerful seduction of political engagement, particularly in democracies, is the illusion that true power is in Washington or Ottawa or Asunción or Tehran. Yet Christians believe that history is carried forward by the church, not the state. How would you see the world differently if your primary source of global news came from church leaders around the world or from Christian relief and service workers in other countries rather than from Fox, CNN, or the echo chambers of social media?

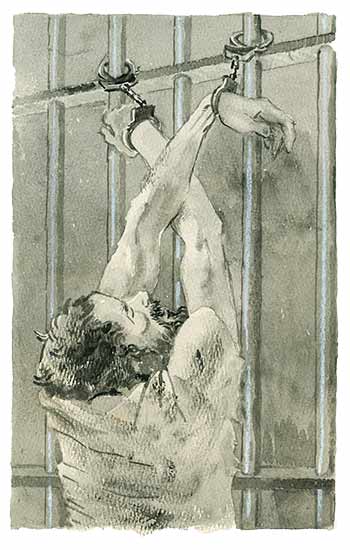

In the United States during World War I, several Hutterite men were arrested and imprisoned on Alcatraz Island for their refusal to don military uniforms after being drafted. Two brothers, Michael and Joseph Hofer, died as a result of the treatment they received in prison. Artwork by Don Peters

Third, Anabaptist Christians should approach their political witness in a posture of confession and humility. Anabaptist Christians can, and should, speak out against violence, oppression, and injustice wherever it occurs. But we should do so in the awareness of our own ongoing complicity in systems and structures that fall short of the kingdom of God. We do not occupy some high ground of absolute moral purity.

Fourth, Anabaptist Christians should resist the seductive argument that “responsible” political witness must always take the form of electoral politics, public protest, lobbying campaigns, and legislative action. The allure of theocracy – either of the left or the right – is powerful; Christians who are quick to denounce Muslim sharia law are often blind to their own secret desire to create Christian commonwealths of their own, always with the best of intentions. The most powerful form of Christian lobbying is likely the testimony of embodied practices. Christians bear political witness whenever they nurture healthy relationships within their families, support thriving schools and voluntary associations, or pray for people in positions of political authority. They testify to their deepest political allegiances when they stand alongside people on the margins, speaking out on behalf of the poor, the refugees, the dispossessed and those without a voice. In my community, a disproportionate number of Anabaptist Christians are active in homeless shelters, afterschool programs, adult literacy initiatives, and in healthcare projects that reach out to the most vulnerable members of our communities. Anabaptist Christians have demonstrated a special interest in creative forms of conflict resolution. The Victim-Offender Reconciliation Program – a community-based initiative started by Anabaptist Christians – has been enthusiastically supported by courts throughout the United States and now has local chapters in hundreds of communities and twelve countries. And some Anabaptist Christians are called to challenge oppressive and violent regimes through nonviolent direct action. There are no guarantees that pacifism will always work as a political strategy in such cases. But in contrast to the quick solutions promised by defenders of “legitimate violence,” Christians know that peacebuilding is a long process, requiring a deep understanding of culture, an appreciation for the complexities of human nature, a recognition that relationships must be built on trust and, ultimately, a capacity for patience.

The most powerful seduction of political engagement is the illusion that true power is in Washington or Ottawa or Asunción or Tehran.

Finally, Anabaptist Christians engage in political witness when they offer public expressions of lament and hope. Public lament is a reminder that violence is always an aberration, an unwelcome intrusion, into the world as it should be. On the other side of lament is the hope of an alternative future, the hope expressed by millions of Christians every day when they pray: “thy kingdom come; thy will be done; on earth as it is in heaven.”

In all these and many other ways, Anabaptist Christians embrace their political responsibilities – not primarily as citizens, or as representatives of political parties, or as a lobby group shouting to be heard, but as ambassadors of the Prince of Peace who came as a servant, welcomed children and foreigners into his circle, and taught us to love our enemies.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

George Marsh

I greatly enjoyed this essay. It reminds me of a section in Paul's Second Letter to Timothy: "Beloved, I remind you to stir into flame the gift of God that you have through the imposition of my hands. For God did not give us a spirit of cowardice, but rather of power and love and self-control." (1:6-7) Christians understand the "power" is God's power, to transform for the better; not "power over" but "power for."

allan

Jesus' ministry was apolitical' 'My kingdom is not of this world'. 'Let the dead bury their dead - follow Me."

Dan

I think this was overall a very well-chosen and thoughtful article. One aspect I might add is that from a Christian perspective we would not be in thrall to a nation or government. He touches on this when he says not to think that real power lies in Washington etc.; of course realistically unimaginable tangible power lies there, but although power is dangerous at best, there's also an irresistible outgrowth of sanctity around power. It's this that we can easily find ourselves in thrall to: that a nation has "a sacred right, a sacred duty, is a beacon of, has a right to exist, that's not who we are, is the greatest" etc. I think that when we think about these common sentiments, we realize that most of them relate to the supposed good and humane life enjoyed by people within a nation's borders. It's a small but I think important distinction between advocating, voting, petitioning, or demonstrating for a position because "that's who/not who we are" or because it's the humane position. Of course the example of the government of Paraguay appointing ministers (seemingly) specifically because they are Mennonites is all kinds of problematic. Should me and my family then start attending a Mennonite church to climb the social ladder? Furthermore, what happens when one person makes preferential by virtue of his power a certain brand of honesty, humanity, etc., at the cost of other alternate expressions of these values; as happened in Paraguay when the president decided that the "Mennonite brand" of social and economic programs was the one to go with? I would guess that other people would feel their opinions were ignored, and also that certain Mennonites in Paraguay found that their practices and even faith had become political, tied now to the inevitable poll numbers, dealmaking, and sex scandals of the administration. That ties into my final thought on all this: that the political is such a dangerous thing because it's an animal with its eyes in its stomach: it has to devour a thing before it can see if it's real. By this I mean the inevitable that we can't see anything: a doctor, a train, a school, an art form, God, Allah, without knowing its political standing. There's always the question even "Is your church liberal? Is it conservative? Is it progressive? Is it open? Is it modern? Is it traditional?" The refusal or even the attempt to see things in the light of a non-political spectrum, to not give everything to Caesar, is probably very important and probably impossible.

Rowland Stenrud

The point of non-violence should be that of rejecting idolatry. I refuse to kill on behalf of the state because such killing would be tantamount to worshipping the state. On the other hand, if someone came into my neighborhood and started killing people, I would use violence, if needed to stop him from his killing spree. The problem with Anabaptist non-violence is that it is a virtue taken to an extreme level. It became an object of worship, it became idolatrous. God was not doing evil when he killed every man, woman and child with the Great Flood of Noah's day. The people had become wicked, so wicked that they had to have been most miserable. The biblical doctrine of universal salvation redeems this Divine act of violence. God, through his tools of Judgement and the Lake of Fire and through the loving faith and obedience of Jesus in going to the cross, will give eternal life to all of his victims of Divine violence including the violence of old age. One cannot be a true lover of one's enemies, a true non-violent Christian while supporting the doctrine that God will torture his enemies in a place called hell for no purpose but to cause the unsaved pain. Jesus went to the cross to save all people, not just some. While the minority of human beings are saved on this side of the grave, the rest are saved on the other side. God has a good purpose for resurrecting the wicked such as the victims of the Great Flood. Belief in hell or annihilation as the final destiny of the lost contradicts any devotion to non-violence.

Brian Dolge

I am surprised you did not discuss the thought of Mark Van Synwick and the Mennonite Worker, an Anabaptist centered witness in an urban context which is refreshingly distinct from the rightist slant of so many faith based political groups.

Bryce Staniland

Well worth reading. A timely reminder of the social and political aspects of the Christian Gospel that are often forgotten or ignored.