Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Editors’ Picks Issue 24

-

Van Gogh Comics

-

Boys Aren’t the Problem

-

The Woman Who Carried Me

-

Samuel Ruiz García

-

Christian Nonviolence and Church History

-

American Muslims: Race, Faith, and Political Allegiance

-

Ministers and Magistrates

-

Pick the Right Politics

-

Editor’s Postscript: Notes from the Lockdown

-

Readers Respond: Issue 24

-

Family and Friends: Issue 24

-

What Goes Up

-

The Politics of the Gospel

-

What Are Prophets For

-

Bishop Ambrose

-

The Anabaptist Vision of Politics

-

Jakob Hutter

-

The Bruderhof and the State

-

Saint Patrick

-

Reading Romans 13 Under Fascism

-

Holding Our Own

-

Living with Strangers

-

Tolstoy’s Case Against Humane War

-

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Conscientious Objector”

-

Oscar Romero

The Martyr in Street Clothes

An icon reveals the hidden power of a friendship beyond boundaries

By Stephanie Saldaña

March 25, 2020

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

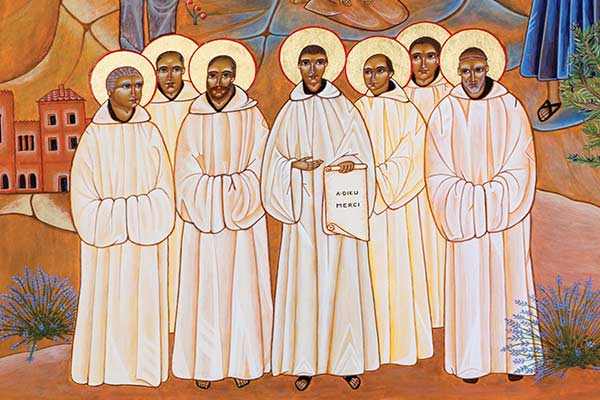

A copy of the icon sits on my desk, calling to me: the nineteen martyrs of Algeria, who gave their lives in love during the civil war of the 1990s. Here they stand gazing at me, in the loose robes they might have worn when visiting the market, nursing the ill, teaching, or saying Mass. Monks and nuns, priests, a bishop, all with their faces haloed. Simple, humble, their feet firmly planted in the Algerian soil.

The icon of the nineteen martyrs of Algeria. Written by Odile, Petites soeurs de nazareth et de l'unité. Courtesy of the Diocese of Oran, Algeria.

It is rare that beatification happens so quickly, that I can call “Blessed” those who lived and died in my own lifetime, those I might once have passed in the street. Yet here they are, not thirty years after they were martyred, dying along with nearly 200,000 of their Algerian neighbors. Their beatification, held on December 8, 2018, in Oran, serves as a stark reminder that holiness lives among us, that saints do not belong to other eras but to our lives, our friendships, our own streets.

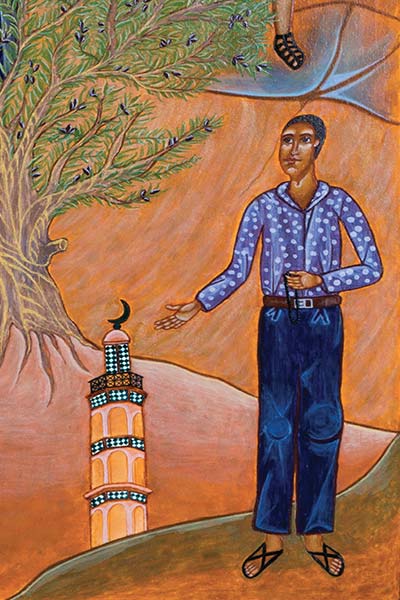

But it is not their nineteen faces that draw me in most. Instead I find myself turning towards a twentieth figure – a young man, standing in the corner, wearing jeans, sandals, and a blue shirt with polka dots. He has no halo; its very absence pulls me to him. He gestures toward the minaret of a mosque. How did he come to be on this icon of the Christian martyrs of Algeria?

In time, I learn that his name is Mohamed Bouchikhi, and that this young Muslim offered his life for his Christian friend, Bishop Pierre Claverie.

The story of how Mohamed came to be on the icon of nineteen Christian martyrs is equally the story of how nineteen martyrs came to be on the same icon as Mohamed, in whose country, Algeria, they chose to live and die. It is the story of Muslims and Christians witnessing to hope together, asking, even in death, to be written into a single frame.

The icon’s most imposing figure is the bishop himself, Pierre Claverie, who stands with a staff in hand, wearing red and white vestments. His journey onto this scene was as unlikely as Mohamed’s. Claverie was born in Algeria in 1938 when it was still a French colony. As the child of French settlers, whose family had lived in Algeria for generations, he would later reflect back on a happy childhood, but also on the “colonial bubble” in which he grew up – raised by loving parents but little aware of his surroundings. He spoke no Arabic and had almost no contact with Muslim Algerians.

He traveled to complete his studies in France, and it was there, as a young student and a seminarian, against the backdrop of the rising Algerian independence movement back home, that Claverie’s worldview was shaken. For the first time, he met those who questioned the French presence in Algeria, angry that they might have to risk their lives in military service there. Claverie became aware that as a Frenchman in Algeria he had participated in a system that excluded his Muslim Algerian neighbors. “How could I have lived in ignorance of this world, which demanded recognition of its identity and dignity?” he asked. “In churches, how could I have so often have heard the words of Christ about loving the Other as myself, as Him, and never met that other?”

Even as many French in Algeria left for France in the wake of Algerian independence, Pierre Claverie experienced a conversion of the heart. He became a priest and asked to return to Algeria – no longer as part of a group in power, but as a common pilgrim bound together with his neighbors. He wanted to rediscover the country of his childhood as he had never known it, to study Arabic and Islam and to give his life to this new Algeria. He wrote: “It’s there that my true personal adventure began – a rebirth.”

“The covenant with God passes through the covenant with the people to whom he gives us.”

Bishop Pierre Claverie

Claverie became part of a transformed church, a diminished group of Christian religious who decided to stay as guests in the house of Islam. They were led by Archbishop (later Cardinal) Léon-Étienne Duval, originally from Savoie in France, who had been sympathetic to Algerian self-determination and had spoken out against the French government’s use of torture. French critics mocked him as “Mohamed Duval.” Unfazed, he took dual French and Algerian nationality to emphasize his devotion to Algerians. “I can summarize my apostleship in Algeria with one word: friendship,” he once said.

Pierre Claverie with nuns of the Sacred Heart in Bikfaya, Lebanon Photograph from the Sacred Heart Archives

“I have called you friends,” Jesus tells his disciples in the Gospel of John, and it was in the spirit of friendship that these clergy stayed on, living with, learning from, and serving their Muslim neighbors, in some cases taking on jobs as teachers, nurses, and librarians. Their faith was bound up in the immediate practice of neighborly love. Claverie wrote: “The covenant with God passes through the covenant with the people to whom he gives us. It is a covenant lived in the way Jesus lived his covenant with the men and women of Palestine – as a servant, and not as a master; in giving one’s life rather than lessons.”

These Christians harbored no desire to proselytize. Claverie wrote: “I not only accept that the Other is the Other, a distinct subject with freedom of conscience, but I accept that he or she may possess a part of the truth that I do not have, and without which my own search for the truth cannot be fully realized.”

During his consecration as bishop in 1981, he thanked the Algerians of his childhood, whom he had at last come to know, for revealing some of these hidden truths. “My Algerian brothers and friends,” he said, “I also owe it to you that I am who I am today. You have welcomed me and sustained me by your friendship. I owe it to you that I have discovered the Algeria that was still my country, but where I had lived as a foreigner throughout my youth.”

No longer a foreigner, in his years as a priest and bishop of Oran, he celebrated Mass in Arabic, engaged in dialogue with Islam, and could be recognized wearing a stole on which was written in Arabic Allah Muhabba: God is love.

Wanting to know more about Bishop Pierre Claverie and Mohamed Bouchikhi, I travel across Jerusalem, where I live, to meet Father Jean-Jacques Pérennès, a Dominican priest who is director of the École Biblique et Archéologique there. Pérennès lived in Algeria for years and was a close friend of Bishop Pierre, who ordained him. He has written Claverie’s biography and took part in the historical commission in charge of the beatification process for the nineteen martyrs, sifting through nearly five thousand pages of documents about their lives. I find him in his office, surrounded by books. When I show him my framed copy of the icon, he leads me to a copy that he also keeps, and we study the faces together.

Priests, nuns, teachers, servants. Killed at work, at home, on the way to Mass. Haloed, but many of them wearing the humble clothes of their daily lives. Nineteen ordinary people.

“They weren’t perfect,” Pérennès tells me. “It shows that holiness is possible for people like us.”

When the civil war between an Islamist insurgency and the Algerian military began in the early 1990s, in what is often referred to as the Black Decade, the religious were not the first to be assassinated. Islamist extremists first targeted those who represented the state, such as judges and policemen, then those who represented an open society. Finally, they started to attack foreigners.

“We didn’t think that the religious would be killed,” Pérennès tells me. “The first two killed, on May 8, 1994, came as a big shock.”

Each member of the clergy and of the religious orders in Algeria had to decide if he or she would stay; Pérennès recalls the bishops meeting with the members of the religious orders and insisting that they feel no shame if they decided to leave. Some were having nightmares. In other cases, their families were pressuring them to come back home. He estimates that two-thirds of the religious decided to remain in solidarity with their neighbors, who were being killed by the thousands. “They said: ‘We choose freely to remain in this country, despite all of the risk, out of love for the gospel, for the church, and for this country to whom we have been sent.’”

They did not see themselves as members of a persecuted church. They lived as their neighbors lived – in great danger. They died among others who were also dying: Algerian intellectuals, doctors and lawyers, foreigners working in the country, artists and writers, Muslim imams who denounced violence, and women and children.

“We must not be afraid. We have to live the present well. The rest does not belong to us,” said one nun not long before she was killed.

As the violence mounted, Bishop Pierre reflected on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s notion of “costly grace.” In a letter written in 1994, he wrote: “We will remember this Christmas that the path of hope passes through the cross.”

Now my eyes are drawn to the seven figures in white robes gathered at the bottom of the icon: the most famous of the martyrs, memorialized in the film Of Gods and Men, the Trappist monks of the monastery of Notre Dame de l’Atlas in Tibhirine. Already while they lived, Cardinal Duval had called their vocation the “lungs of the Church of Algeria” – their simplicity and dedication to prayer respected by their Muslim neighbors, who themselves prayed five times a day.

I recognize the abbot, Christian de Chergé, in the center of the seven, holding the text of his Testament, a farewell letter expressing his gratitude towards Algerians and forgiveness towards his killer, whom he calls his “last-minute friend.” I squint to read the French text on the icon: Adieu, merci.

The seven martyred monks of Tibhirine with a friend Photograph © SIPA

Goodbye. Thank you. Why such gratitude in the face of death? Hidden behind the story of Father Christian’s life and vocation had also been the transformative witness of a pious Muslim friend named Mohamed – who might just as easily have been pictured on the icon too.

The story goes roughly like this: as a seminarian in 1959–61, the future Father Christian had carried out his French military service in Algeria, during which time he befriended Mohamed, a rural policeman. The two had often gone on walks together, discussing their respective faiths. Christian was moved by the depth of his friend’s piety, which encouraged him to deepen his own. Mohamed had once said to him: “You Christians, you do not know how to pray.” Christian received those words not as a criticism but an invitation, and he remembered them for the rest of his life.

“We are protecting our freedom to love everyone, because that is our choice. Christians are not the only martyrs of charity. Muslims are, too.”

Christian de Chergé

One afternoon, when the two of them were walking, they were attacked by a group of rebels. Mohamed defended Christian, and as a result the Frenchman was left unharmed. But the next day, Mohamed was found killed. That sacrifice was the source of the young seminarian’s vocation. He became a Trappist monk, and called the monastery in Tibhirine “a place to pray among those who pray.” He led a Muslim-Christian dialogue group and prayed with the Quran as well as the Bible. And he always remembered his friend Mohamed, who had given his life in exchange for Christian’s own and thus given witness to “the greatest love of all.”

Later, Fadila Semaï, a French journalist born to Algerian parents, went searching for the story of this Mohamed, naming her book L’ami parti devant after the one Father Christian referred to as “the friend who departed in front,” whom she calls his friend “without a face.” In the offering of this unknown Mohamed’s life, she discovered a love unbound by religion, colonialism, or nationalism – a love that Father Christian would take up, embody, and one day offer back to his Algerian neighbors in return.

At the height of the later civil violence, Father Christian said, “We are protecting our freedom to love everyone, because that is our choice. Christians are not the only martyrs of charity. Muslims are, too.”

Christian de Chergé and his fellow monks were kidnapped and killed in 1996. Cardinal Duval, by then retired, was heartbroken by the news and died a week later, so that his casket was also wheeled out along with those of the seven monks when the funeral was held. In his Testament, written before his capture to be opened if he died by violence, Father Christian paid tribute to his beloved country, calling Algeria and Islam “a body and a soul.”

When i first saw that twentieth figure in the corner of the icon, displayed during a Mass for the martyrs in Jerusalem, I asked a woman standing beside me: “Is that Christian de Chergé’s beloved friend Mohamed, the one who died for him and who became the source of his vocation?”

“No,” she answered. “That is Bishop Pierre’s friend Mohamed.”

And I, who had thought that I knew the story well, asked: “Wait … Pierre Claverie had a friend named Mohamed, who died for him, too?”

These witnesses become signs of hope, reminders of a love that outlasts death.

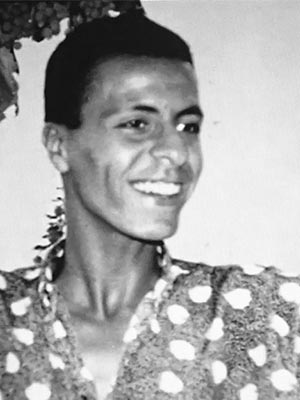

Here at last enters the story of Mohamed Bouchikhi, whose kind face and outstretched arms invite me in every time I meditate on the icon where he stands. Mohamed grew up living beside the presbytery of the church, where he befriended the parish priest and the religious sisters. As a youth he used to volunteer to be of service to the church however he could.

As he grew older, Mohamed especially loved to run errands by driving the church’s white Peugeot. In one of the photographs we have of him, Mohamed stands proudly next to the car, wearing that same blue polka-dotted shirt, a smile on his face. He sometimes picked up Bishop Pierre from his meetings, despite the increasing danger. Pérennès tells me that Bishop Pierre had been receiving threats, and so on one occasion, worried about Mohamed’s safety, he asked him to consider stopping his help. The question apparently made Mohamed upset.

Pierre, for his part, told a friend of his that “if it’s just for one like Mohamed, it’s enough of a reason to stay.”

On the fateful night of August 1, 1996, Mohamed drove to meet Bishop Pierre at the airport. The bomb blast when they arrived at his residence hit them both at once, their blood mingled on the ground.

It was later discovered that Mohamed had recorded his own testament in a notebook, in preparation for this moment:

Bismallah, al-Rahman, al-Raheem. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.

Before I pick up my pen, I say to you: Peace be upon you. I thank you who will read my diary, and I say to each one of those whom I have known in my life that I’m thankful. They will be rewarded by God on the Last Day. Farewell to those who I have harmed, I ask your forgiveness. And may those who have forgiven me find pardon on the Day of Judgment. Forgive me for any time that an evil word has passed my lips, and I ask all of my friends to forgive me on account of my youth. Yet, on this day on which I am writing to you, I remember the good that I have done in my life. May God, in all of his power, help me to surrender to him, and grant me his tenderness.

“They shared their friendship and they shared their death,” Pérennès tells me. When the beatification of the martyrs of Algeria took place two decades later in Oran, the official icon of the martyrs was unveiled. And there was the figure of Mohamed Bouchikhi, standing quietly in the corner, pictured with the other nineteen friends.

Mohamed Bouchikhi Photograph courtesy of the author

I ask why they depicted him without a halo. Pérennès tells me this is a gesture of respect, a reflection of their desire to honor him without annexing him. “He’s a Muslim,” Pérennès says firmly. “We’re not going to say that he’s Christian. But it’s a way of saying that being a Muslim, he has the same quality of love, and the capacity of giving himself, the same generosity. It’s not restricted to Christians, the ability to give your life for others.”

The emotion is evident in his voice when says: “In our hearts there were twenty.”

There is no greater love than to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. These words crown the top of the icon, just above the face of Jesus who said them, the twenty-first friend.

Mohamed, full of love of God and in full witness of his Muslim faith, died for his friend Pierre. And Pierre, full of the love of God and in full witness of his Christian faith, died for his friend Mohamed. Just as Christian de Chergé’s friend Mohamed died for him, and Christian later died for his Muslim friends. These witnesses become signs of hope, reminders of a love that outlasts death. It is a love on pilgrimage, a love still doing its work in us, the living, taking us by the hand and leading us into an ever-widening frame, where we might know truly that we belong to one another.

Quotes from Pierre Claverie are taken from A Life Poured Out: Pierre Claverie of Algeria by Jean-Jacques Pérennès and Lettres et messages d’Algérie by Pierre Claverie.The story of Christian and Mohamed is told in The Monks of Tibhirine: Faith, Love, and Terror in Algeria by John W. Kiser and Christian de Chergé: A Theology of Hope by Christian Salenson.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Danny

I read the story 'The Martyr in Street Clothes' at the kitchen table, as the children played in the front room and Joy studied upstairs. At first I inwardly cried because I didn't want the children to see my upset, then allowed the tears to run down my cheeks freely. I cried not for loss but because of the love, respect and sacrifice that people of different faiths showed each other. And also for all those, of all faiths, that have lost their lives to Covid-19. Thank you again for this enlightening piece of writing.

Judith

In my mind's eye Mohamed Bouchikhi has a halo!