Subtotal: $

Checkout

Comrade Ruskin

How a Victorian visionary can save communism from Marx

By Eugene McCarraher

August 26, 2019

Available languages: Español

Whose is the Wealth of the World but yours?” Thus did a radical firebrand address Britain’s industrial working class in the summer of 1880, urging them to seize the fruits of their labor: “Do you mean to go on for ever, leaving your wealth to be consumed by the idle, and your virtue to be mocked by the vile? The wealth of the world is yours; even your common rant and rabble of economists tell you that – ‘no wealth without industry.’ Who robs you of it, then, or beguiles you?”

The militant who penned these words was not Karl Marx, though he was then in London working on the last two volumes of Capital. Instead it was a self-professed “violent Tory of the old school” who held the post of Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford. His name was John Ruskin.

Ruskin had been writing open letters to “the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain” since the early 1870s. He titled these missives, somewhat enigmatically, Fors Clavigera, or “Fortune the Nail-bearer.” They covered an array of subjects: work, property, politics, and art. Addressing the working class as “My Friends” at the beginning of every epistle, he avowed his old-school Toryism in the tenth letter, proudly declaring “a most sincere love of kings, and a dislike of everybody who attempted to disobey them.”

Yet two months earlier, in a previous letter, the lover of monarchs and hater of rebels had proclaimed himself a “communist,” one who was “reddest also of the red.” To be sure, Ruskin used the word communist in a sense very different from the one it would carry after the Russian Revolution. In 1871, alarmed by (false) reports that the insurgents of the Paris Commune had destroyed many of the city’s churches and monuments, he rejected what he called “the Parisian notion of communism” – the belief that all property should be common property. Instead, he wrote, “we Communists of the old school think that our property belongs to everybody, and everybody’s property to us.” Therefore even “private” property was common in some way (one that Ruskin, alas, didn’t specify). Moreover, he believed that “everybody must work in common, and do common or simple work for his dinner.”

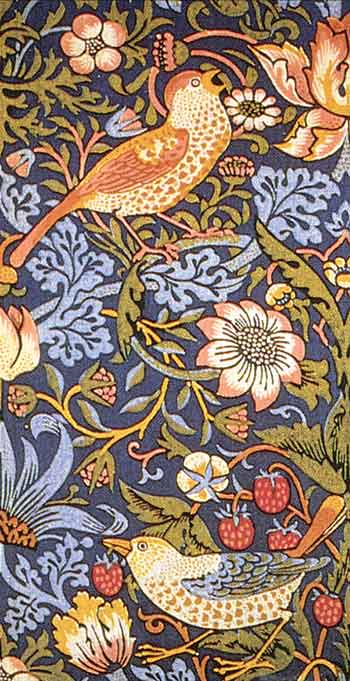

William Morris, Strawberry Thief, printed textile, 1883

Ruskin scholars generally pass over this communism as incoherent or ironic. But I want to argue that it was neither. Instead, it represents a road not taken in the history of movements for a just social order. Today, amid renewed outrage over the depredations of globalized capitalism, it’s high time to rediscover Ruskin’s vision for how people should live and work together.

Like Marx and other communists of the nineteenth century, Ruskin was addressing some of the most intractable dilemmas of capitalist modernity. These included the expansion of industrial production at the expense of individual control and creativity, an enormous increase in wealth and productivity alongside poverty and despoliation, and an ideal of limitless technological progress that threatened to reduce the heritage of the past to oblivion. They also reflected a new, money-defined view of what it means to be human, one in which men and women are no longer valued as images of God but rather as sources of profitability and efficiency.

Marx believed that the resolution of these conflicts lay in the harsh but ultimately liberating trajectory of capitalism itself, whose own internal contradictions would necessarily goad the proletariat into revolution. (This is the deterministic notion at the heart of so-called scientific socialism.) By contrast, Ruskin rooted his opposition to the tyranny of mammon in a sacramental humanism that was emphatically Christian. For Marx, communism would be the tragicomic endpoint of capitalist development. But for Ruskin, communism represented “the Economy of Heaven”: a society that would recover the artisanal mastery destroyed by mechanization and would elide the distinction between private property and the common good. With the freely creative person at its center, Ruskin’s kind of communism was to be a political economy of love.

The Un-Convert

Like so many other scourges of the bourgeoisie, Ruskin grew up in a bourgeois family. His father, John James, was a successful wine merchant who was fond of Romantic writers, especially Lord Byron and Sir Walter Scott. His mother, Margaret, was a rigorous evangelical who insisted on his memorizing large parts of the Bible. Thanks to his father’s lucrative business, Ruskin had the leisure to read and travel widely. Apart from scripture, he immersed himself in Homer, Shakespeare, Gibbon, and Bunyan, and he visited Scotland, France, Belgium, Germany, and Italy before he was fifteen. Enthralled by the paintings of J. M. W. Turner, young John also took to drawing and writing about nature, filling notebooks with sketches and publishing his first articles on art before he was twenty.

Despite his strict evangelical home and outwardly pious demeanor, Ruskin doubted the faith early on: his devotion “was never strong,” he once told a friend, and in his autobiography he confessed that, at age fourteen, he had mused that while angels might have visited Abraham, “none had ever appeared to me that I knew of.” He lived with this ambivalence while a student at Oxford. Over the 1840s and 1850s, as his intellectual career accelerated, Ruskin slowly sloughed off the faith of his upbringing, becoming, as he put it, “a conclusively un-converted man.”

Yet Ruskin’s “un-conversion” was from evangelicalism, not from Christianity. His evolution from art critic to political economist – or rather, his blend of the two vocations – marked an effort to pursue the traditional calling of the prophet in modern times. Like many other Victorian intellectuals, Ruskin was shaken by discoveries in geology, biology, and the historical criticism of the Bible. Some of his contemporaries – Herbert Spencer, Charles Bradlaugh, T. H. Huxley, George Eliot – embraced secularism, while others – John Henry Newman and the Oxford Movement – affirmed orthodoxy. A third group, which included William Blake, William Wordsworth, and Thomas Carlyle, pioneered a Romantic religiosity that perceived the supernatural within nature: Blake’s “heaven in a wild flower” and Wordsworth’s “sense sublime / of something far more deeply interfused.” The Romantics were the modern heirs of the Christian sacramental imagination – the belief that visible, material reality can mediate the grace of God. This was the faith that Ruskin came to embrace.

Conveyed in a Christian idiom, Ruskin’s Romanticism surfaced first in his five-volume Modern Painters (1843), and then leavened his forays into social criticism and political economy. Artists such as J. M. W. Turner, he asserted in volume one, perceive in nature “that faultless, ceaseless, inconceivable, inexhaustible loveliness, which God has stamped upon all things.” Beauty, he wrote in the second volume (1846), “whether [it] occur in a stone, flower, beast, or in man … may be shown to be in some sort typical of the Divine attributes.” “In the midst of the material nearness of these heavens,” he declared in volume four (1856), we “acknowledge His own immediate presence.” Because Ruskin saw the sacred in nature, he saw it in humankind as well. “The direct manifestation of Deity to man is in His own image, that is, in man,” he wrote in volume five (1860). “The soul of man is a mirror of the mind of God” – a mirror, he rued, “dark distorted, and broken.”

Work and Workers

The broken mirror of human divinity was most evident, for Ruskin, in the industrial division of labor. As a host of historians has explained, the Industrial Revolution that commenced in the mid-eighteenth century was a social process as well as a technological one. Driven by the capitalist imperative to lower costs and increase profits, manufacturers realized that they needed to master the production process itself. Succumbing to competition from the early industrialists, artisans and craftsmen who controlled their own tools were dispossessed from the means of production and transformed into wage laborers in factories – “proletarians,” in Marxist terms. Now that the link between workers and their tools was broken, labor could be “degraded,” rationalized, and broken down into discrete elements – and then relocated from humans to machinery. In this way, the industrial division of labor eroded artisanal skill by mechanizing or automating production. The factory embodied capital’s power over the minds and movements of workers. To early industrialists, this was part of the point. In the words of Andrew Ure, who in 1835 wrote one of the first texts on industrial management, factory work would not only enhance profits and productivity but also “restore order among the industrious classes” and “strangle the Hydra of misrule” (The Philosophy of Manufactures).

William Morris, Medway, printed textile, 1885

Early critics of industrial capitalism objected at least as much to dispossession and degradation as they did to poverty and misery. Already in the Luddite uprisings in the 1810s, hundreds of weavers in Nottingham and Yorkshire smashed textile machinery as a protest against mechanization. Around the same time, utopian socialists such as Charles Fourier lamented the elimination of play and creativity from work – the logical culmination of industrial labor, the literal de-humanization of production.

The young Marx analyzed the dehumanizing effects of industrialization in some of his writings of the mid-1840s. The essence of humanity, he contended, was “free, conscious activity,” a versatile and even artisanal creativity that “forms things in accordance with the laws of beauty.” If I create “in a human manner,” Marx writes, I make something that bears the mark of “my individuality and its peculiarity”; I delight in satisfying your need, and my personality is “confirmed both in your thought and your love”; I realize “my own essence, my human, my communal essence.” The ultimate aim of work is not just production, but the flourishing of a good human life.

Capitalism renders such flourishing impossible by “alienating” the worker from his essence. Alienation is, for Marx, not primarily a psychological malady but rather a social and material deprivation. Because the capitalist owns and controls the means of production – which is to say, for Marx, the means of humanity – he takes for himself not only the wealth that the worker produces, but also “the very act of production itself,” the worker’s mental and manual virtuosity. Alienation is Marx’s account of the dispossession and degradation of craftsmanship that the capitalist achieves through the industrial division of labor.

But because Marx believed in “progress” through the dialectical unfolding of history, alienation was, in his view, a progressive step toward the destination of communism. Because it enabled technological innovation and generated material abundance, the arduous and often violent process of proletarianization was, Marx insisted, historically necessary and beneficial. Placing the industrial proletariat on what Hegel had called “the slaughter-bench of history,” capitalist automation made martyrs of workers for the sake of a golden future: the communist utopia of abundance, free time, and mechanized emancipation from labor. By the time Marx published the first volume of Capital (1867), machinery was for him both a “demon power” and a historical vehicle to the “realm of freedom.”

While Ruskin, like the young Marx, thought of human work in artisanal terms, his communism stemmed from a very different assessment of the impact of industrialization. This requires some explication. Despite claiming to be a “violent Tory,” Ruskin was no reactionary, as many of his critics (then and now) have contended. “I am not one who in the least doubts or disputes the progress of this century in many things useful to mankind,” he insisted (The Two Paths, 1859). What mattered was how to distinguish “the progress of this century” from regression into barbarism. To Ruskin, the industrial division of labor, far from liberating human beings, constituted their disfigurement and profanation. He argued that mechanization – mandated by the imperative of profit – effected “the degradation of the operative into a machine” (The Nature of Gothic). Human beings were ingenious, intrepid, and imperfect; the precision of motion dictated by industrial machinery reduced people to machines themselves. “You must either make a tool of the creature, or a man of him. You cannot make both.” If you want pliant, efficient workers, “you must unhumanize them,” Ruskin warned – which meant that you must desecrate the image and likeness of divinity.

John Ruskin in 1863

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Health and Illth

In 1862, Ruskin wrote his most cogent and controversial work on political economy, a collection of four essays titled Unto This Last. It sketches out the theological groundwork for his Romantic communism. Going further than Carlyle, who called economics “the dismal science,” Ruskin refused to even acknowledge economics as a science, likening it to “alchemy, astrology, witchcraft, and other such popular creeds.” Economics is untrue, not just dismal, he maintained, because it got human nature wrong: a human being is not a rational utility-maximizing calculator but rather “an engine whose motive power is a Soul.” Because its starting point was false, economics was like “a science of gymnastics which assumed that men had no skeletons.” As with human beings, so with the rest of the world: everything “reaches yet into the infinite,” Ruskin mused, and the earth resonates with “amazement” – a measureless, inexhaustible wonder at what Gerard Manley Hopkins would call the grandeur of God.

This keen sense of the sacred in nature and in humankind was the basis for what Ruskin dubbed the “real science” of production and consumption. If the “Soul” was what made us reach yet into the infinite, then true political economy was a science of desire, for “the desire of the heart is also the light of the eyes.” The real science of the “Economy of Heaven” taught us how to “desire and labor for the things that lead to life” – life meaning not just survival, but the cultivation of all our powers of “love, of joy, and of admiration.” The implication, of course, was that capitalist economics is a science of death – a necro-science that taught us to desire competition, envy, avarice, and corruption. Repudiating these “Laws of Death,” Ruskin famously insisted that “there is no wealth but life.”

Life as true wealth is the key to understanding Ruskin’s distinction between wealth and what he called “illth.” Conventional economics measures wealth quantitatively, for example as the tally of goods and services that make up the Gross Domestic Product. But Ruskin’s definition of wealth was qualitative: “the possession of the valuable by the valiant.” Such wealth existed in a connection between the nature of a thing and that of its possessor; a valuable object became valueless in the hands of a vicious person. Pursued for the sake of virtue, the true end of wealth was a bounty of “full-breathed, bright-eyed, and happy-hearted human creatures.” And since Ruskin favored “great quantity of consumption,” he was no ascetic; indeed, consumption, he insisted, is “the final object of political economy.”

Yet happy-hearted consumption is far different from what we today call consumerism. Modern consumerism is really a covert culture of production, since profit, not pleasure, is its ultimate goal; its incessant stimulation of desire and dissatisfaction is a means to make money, not to ensure our fulfillment. That is why, for Ruskin, much of capitalist wealth is really “illth”: either because it is harmful in itself, or because the value of an object is mismatched to the virtue of its possessor. Such “illth” wreaks “devastation and trouble in all directions” – which is what one would expect from a fraudulent science.

Christian Communism

Ruskin’s sacramental economics forms the backdrop for his communism as described in Fors Clavigera. While both Ruskin and Marx identified the dislocation of workers from control over production as the fundamental injustice of capitalism, Ruskin’s “old-school” communism parted from that of Marx in two significant respects. First, for Marx, communism would be the consummation of a promethean project of industrial development – a project that actually required “mammon-service,” exploitation, and indignity. For Ruskin, by contrast, communism defied the historical necessity of avarice and its industrialized despotism. Second, where Marx emphasized communism as a form of property – common ownership – Ruskin emphasized communism as a principle of morality – as pre-modern communists had put it well before Marx, “from each according to ability, to each according to need.”

The Marxist objection to Ruskin’s communism has often been that it idealizes a petty-bourgeois economy of small producers, whose private property relations subvert all their earnest professions of charity. To a Marxist, this is reactionary – capitalist consolidation of the economy is necessary to prepare the way for the collectivization of industry, and eventually, for the communist utopia. (Meanwhile, Ruskin’s Christian morality is considered an ideological enemy, blinding workers to the need for revolution.) When it comes to property, the Marxist and the capitalist are thus in agreement: there is either private, capitalist property or common, collectivized property – no other form of property exists. Hence the puzzlement about Ruskin’s communism: to Marxists and to capitalists, it’s either a disembodied moralism with no effect on the real world, or it’s merely an ironic gesture intended to unsettle complacent readers.

William Morris, Tulip and Willow, printed textile, 1873

But recall Ruskin’s shorthand definition of communism: “our property belongs to everybody, and everybody’s property to us.” What this suggests is a form of property that fudges the distinction between private and collective; indeed, it suggests that private property is never really “private.” Anything but ironic, Ruskin’s communism forces us to reconsider what we mean by “property” in the first place. As the anthropologist David Graeber reminds us, “property is not really a relation between a person and a thing. It’s an understanding or arrangement between people concerning things.” (Someone alone on an island, he muses, doesn’t worry about property rights.) If property is thus always a social relation, then property is private only because we’ve all agreed – or been forced to accept – that it should be. So it’s perfectly possible to imagine property systems in which what’s mine is yours, and what’s yours is mine, depending on how we’ve defined our relationship.

There is a name for a form of social relation in which a person or people can claim rights to objects “owned” by another: usufruct. It’s common among archaic and tribal peoples: I own a tool, but if you need it, it’s yours as long as you don’t damage it. Ownership depends on use; property is a kind of social trust that we’ll all use things for the common good. As vehemently as most Christians believe that private (read: capitalist) property is part of the essence of creation, usufruct was a governing principle among ancient and medieval Christian writers. It’s there in Luke’s account of the early Christians (“No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had”); in Saint Basil’s injunction about surplus goods (“The bread that you keep belongs to the hungry, the cloak in your closet to the naked”); and in Saint Thomas Aquinas’s argument for the “universal destination of goods.”

Continuing in this Christian vein, Ruskin’s communism is usufruct applied to the means of production: ownership of any enterprise that produces goods or provides services – “wealth,” in other words – hinges on the value and valiance of the owners. Contrary to the principles of capitalism, anyone who produced or provided “illth” would be disqualified from ownership. At the same time, communist property, in Ruskin’s terms, requires there to be a beloved community of workers – not acquisitive individualists who accumulate profits by undercutting wages, endangering the biosphere, and degrading dexterity and skill. Thus, technological innovation would surely take a different form in artisanal communism, with “productivity” less important than cultivating mental and manual ingenuity. Nothing could be further from Marx’s vision of total automation and industrialization. Ruskin’s communism is the “Economy of Heaven,” in which men and women fulfill their human nature through the work of their hands.

What We Need Now

So why did Marx’s version of communism triumph over Ruskin’s, at least in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? For one thing, the pace and scale of capitalist industrialization appeared to vindicate Marx’s predictions. As industrialization advanced, the churches, Catholic and Protestant, by-and-large counseled the proletariat to acquiesce in its poverty and degradation. (As Pope Pius XI conceded, “the Church lost the working class.”) The political retreat of the churches allowed Marxist intellectuals and political leaders to claim the banner of working-class resistance. The consequences are only too well known: tyranny, barbarism, and misery, all resulting in millions of deaths.

Ruskin’s communism has had no such bloody legacy. While Ruskin’s indictment of conventional economics endeared him to British socialists, his affirmation of the artisan galvanized the Arts and Crafts movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Indeed, William Morris, the socialist and artisanal polymath who popularized Arts and Crafts, acknowledged Ruskin as his “master.” In Britain and the United States, the movement attracted artists, architects, and urban professionals appalled by the money-driven aesthetics of industrial architecture and design. Eager to nurture beautiful souls as well as make aesthetically appealing products, they established craft schools, workshops, and guilds. Alas, without roots in the working class and a broader vision of social transformation, over time Arts and Crafts became little more than a high-end market for disaffected members of the professional class.

Echoes of Ruskin’s thought reappeared in the 1960s and 1970s, when economists such as E. F. Schumacher advocated “intermediate technology” and “production by the masses” as alternatives to petro-industrial capitalism. In fact, Schumacher insisted that we needed nothing less than “a metaphysical reconstruction” – language that calls to mind Ruskin’s eye for the sacred in both economics and art.

Today the welfare state is in jeopardy throughout the North Atlantic world, automation threatens to wipe out entire classes of employment, and inequality and precariousness have reached levels almost unprecedented in the history of capitalism. That’s why we need Ruskin’s sacramental economics more than ever. It offers an imagination, if not quite a program, for reclaiming the wealth of the world that is ours. We need, not disruptors or innovators, but communists of the old school.

About the artist: The British philosopher and designer William Morris (1834–1896), a leader of the Arts and Crafts movement, was heavily influenced by John Ruskin. In 1892, Morris’s Kelmscott Press issued a hand-printed edition of John Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic, a work that came to be a manifesto for the Arts and Crafts movement. Samples of Morris’s tapestry designs appear throughout this article.

Sign up for the Plough Weekly email

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Forrest Schultz

Ruskin did exactly the same thing in regard to economics and politics that he did in his view of art. Later he turned away from Christianity, and then at the end of his life he returned, which makes it tough to know how to deal with this – "Will the Real Ruskin Please Stand Up!" It is so hard to write about great stuff in Ruskin because someone will jump on you and point out his decadent stage. In regard to economics, Ruskin wrote a very good book called Unto This Last, (Lincoln: U. of Nebraska Press, 1967) which rightly espouses the Gemeinschaft as opposed to the Gesellschaft view of economics in which all of the fundamental terms are redefined. A real eye opener – easy to read and gets right down to the point, which almost all economists ignore.