Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Searching for Safety

-

Stable Condition

-

Editors’ Picks: “In the Margins”

-

Editors’ Picks: “The Genesis of Gender”

-

Editors’ Picks: “Sea of Tranquility”

-

Poem: “Stopping By with Flowers”

-

Poem: “Sugarcane Memories”

-

Poem: “Sonnet Addressed to George Oppen, Arlington National Cemetery”

-

Diaconía Paraguay

-

Winners of the Second Annual Rhina Espaillat Poetry Award

-

Forum: Letters from Readers

-

Charles de Foucauld

-

Covering the Cover: Hope in Apocalypse

-

War Is Worse Than Almost Anything

-

The Last Battle, Revisited

-

The Problem with Nuclear Deterrence

-

A Haven of Olives

-

Book Tour: Time for an Intervention

-

Hoping for Doomsday

-

Radical Hope

-

The Sermon of the Wolf

-

The New Malthusians

-

The Spiritual Roots of Climate Crisis

-

Tradition and Disruption

-

The Apocalyptic Visions of Wassily Kandinsky

-

War and the Church in Ukraine

-

The Griefs of Childhood

-

Everything Will Not Be OK

-

Jesus and the Future of the Earth

-

The Other Side of Revelation

-

American Apocalypse

-

Syria’s Seed Planters

At the End of the Ages Is a Song

To prepare for Christ to return and bring all things to completion, the early Christians sang.

By Joel Clarkson

July 7, 2022

Available languages: español

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

In the days prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as fear built to a froth in news reports, military projections, and NGO preparations, something strange happened: people began to gather, often in public, to sing. In a video captured for the world to see, a crowd of Ukrainian Christians stood in a subway entrance in Kyiv and sang out the spiritual anthem “Prayer for Ukraine” as others passed in a frantic rush before war hit the city. Those of us watching from a distance may have registered cognitive dissonance between the portent of cataclysm and the strangely peaceful crowd, seemingly unaffected by the chaos around them. But for those Ukrainian Christians in the subway, singing was more than mere catharsis or distraction. It was an entry into a posture of expectancy and hope, an engagement with a practice of the early church that many of us have forgotten: the belief that the whole of the created order is made from music, and that to sing is to prepare for the end of the world.

Early Christians expected Christ to return soon and restore the world. The Incarnation initiated a new relationship between world and God, and in Christ’s paschal sacrifice on the cross the curtain of the temple was torn asunder. The rites and rituals reserved for the holy of holies now seeped out into the world, and every activity within creation, from the patterns of prayer to the movement of the sun and moon, became imbued with liturgical significance. Robert Taft writes that in the worship of the early church, “all of creation is a cosmic sacrament of our saving God. … For the Christian everything, including the morning and evening, the day and the night, the sun and its setting, can be a means of communication with God.”

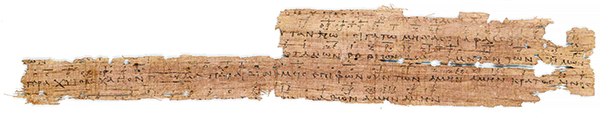

To prepare for Christ to return and bring all things to completion, Christians sang. Some of the earliest hymns reflect this cosmic motif. An example of this is the Oxyrhynchus hymn from the late third century, the earliest instance of Christian hymnody with accompanying musical notation. Though the text has only been maintained in fragments due to the manuscript’s tattered quality, the surviving passage is striking: “… all splendid creations of God … must not keep silent, or shall the light-bearing stars remain behind … All waves of thundering streams shall praise our Father and Son, and Holy Ghost, all powers shall join in …” For the first followers of Christ, the whole of creation became a call to praise, and every act of praise became a participation in the Parousia, the second coming. Even as the first Christians realized that the return of Christ would not necessarily be in their own lifetimes, they retained a sense that the second coming would not occur at a future time, but was an ongoing event in the here and now. Jesus was coming quickly; even creation groaned in expectation, as Romans 8:22 says. To sing was to groan with it.

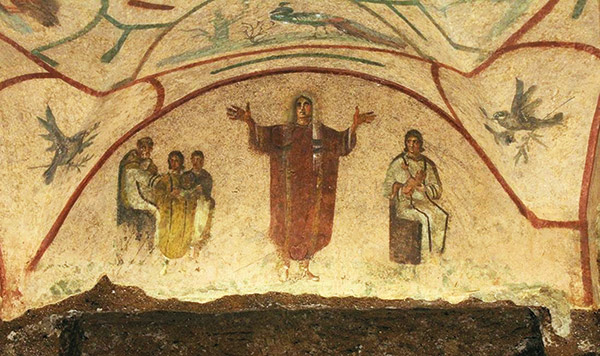

Praying woman, Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome AD 200–400

And there was reason to groan. Christians faced constant threat of persecution and death, and were painfully aware that life was fleeting and time was short. Whether Christ returned, or they found themselves suddenly in his presence due to martyrdom, to these first believers the present age, with all its tribulations, was passing, and the time of the kingdom was near at hand. Nature became a living metaphor of this passage of one age to the next, and the progressions of natural light at dawn and dusk took on an eschatological potency. Cyprian, a third-century bishop of Carthage martyred under Valerian, makes this connection in Treatise on the Lord’s Prayer, instructing Christians on the necessity of praying at dawn and dusk:

For since Christ is the true Sun and the true Day, as the sun and the day of the world recede, when we pray and petition that the light come upon us again, we pray for the coming of Christ to provide us with the grace of eternal light.

Exemplifying this practice is one of the most celebrated hymns of Christian tradition, and one of its earliest: the “Gloria in excelsis Deo.” Drawing on the angelic song to the shepherds in Luke 2:14, this vibrant acclamation, which in time became an integral aspect of the Mass, began as a song praising God for the rising light at dawn. Amid the shadows of affliction and even annihilation, these patterns of prayer, set in song and saturated with the significance of creational illumination, pointed to the One in whom hope might truly be located.

The fourth century introduced a new, complicating dimension into Christian life. With the Edict of Milan in AD 313, Christianity embarked into the uncharted waters of widespread societal acceptance. After decades of the most intense persecution in the history of the church, suddenly Christianity was not only legal but desirable as a religious identity. Christian faith entered the mainstream, and with it, all the patterns of eschatological hope underwent a seismic shift. No longer did the former urgency, precipitated by persecution and death, exist to press Christians into expectant prayer. In its place, a new peril set in: the lull of passivity. How was the church to instill the anticipation made so real in the daily prayer of the first three centuries?

The Oxyrhynchus hymn, on a third-century papyrus scrap, is the earliest Christian song for which we have musical notation.

One answer came in the proliferation of monastic communities, which adopted an ascetic lifestyle, often in remote locales, and formed “rules of life.” These communities continued the practice of daily prayer as a discipline of their vows, under the influence of the fathers and mothers of monasticism such as Anthony the Great, whose life came into profile in the Western church through Athanasius’s Life of Saint Anthony; and Basil the Great, whose monastic settlement in Cappadocia established a precedent of community life, prayer, and mysticism continued to this day, especially in the East. For the vast majority of Christians, however, this unique vocation would remain out of reach. How was the church to respond to the challenges posed by living in an empire replete with worldly vices and material excesses?

Alongside monastic practice, recent scholarship has identified another tradition that scholars such as Taft call a “cathedral office” of prayer, which would have been intended for the laity. Unlike monasticism, which established a pattern of obligatory prayer at set hours throughout the day, this cathedral office centered on dawn and dusk. Like its precursors, it engaged in daily prayer as expectation of Christ, and saw him present in the sign of the rising and setting sun. Vespers, the evening liturgy, expressed this in a unique way. At the hour of dusk, as the shadows set in, a lamp would be brought into the congregation to be blessed. The practice, called the Lucernarium, was a long-established custom throughout the Mediterranean world, in various religious and cultural persuasions. And yet Christians transformed the convention into a potent sign of worship: in that flame they recognized Christ, the true light of the world, whose light would, in time, replace even the sun itself. And the response to that sign, the means through which Christians might participate in that light and make its meaning real in their lives, was to sing.

The most common example of this was the hymn of lamp-lighting in the East, the Phos hilaron, which remains in use in Orthodox vespers liturgy today:

O joyful light of the holy glory of the immortal Father, the heavenly, holy, blessed Jesus Christ. Now that we have reached the setting of the sun and behold the evening light, we sing to God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It is fitting at all times to praise you with cheerful voices, O Son of God, the Giver of life. Behold, the world sings your glory.

In singing this hymn, Christians made themselves part of the living sign of the Lucernarium lamplight, entering the now-and-soon-to-be of its eschatological hope.

Christ lit the way not only in persecution and in comfort, but also in death. In a climactic moment in his biography of his beloved sister, Macrina, Gregory of Nyssa describes her at her bedside, where, even as she enters the twilight hours of her life, she sees and responds to the Lucernarium:

Meanwhile evening had come and a lamp was brought in. All at once she opened the orb of her eyes and looked towards the light, wanting to repeat the thanksgiving sung at the Lighting of the Lamps. But her voice failed and she fulfilled her intention in the heart and by moving her hands, while her lips stirred in sympathy with her inward desire.

For Macrina, Gregory seems to say, the hymn of lamp-lighting, said at dusk, prepares her to enter the dawn of her resurrection in heaven.

Macrina the Younger, the sister of Basil the Great and Gregory of Nyssa (ca. AD 327–379).

From the other side of the Mediterranean comes a strikingly similar story from another beloved saint, this time concerning the Deus creator omnium, a popular fourth-century Western vesperal hymn comparable to the Phos hilaron, written by Ambrose. In his Confessions, Augustine recounts his intent not to publicly grieve his mother Monica’s death, even as his sadness leaves him feeling shattered. In this unrest, Augustine recalls Ambrose’s hymn:

The bitterness of my grief exuded not from my heart. Then I slept, and on awaking found my grief not a little mitigated; and as I lay alone upon my bed, there came into my mind those true verses of Thy Ambrose, for Thou art –

Deus creator omnium,

Polique rector, vestiens.

Recalling these words, Augustine finally weeps, falling into the comforting and compassionate arms of God. In reflecting on the hymn of vespers, Augustine is able to accept grief as the right response to death, seeing God as the one in whom all endings in the brokenness of creation’s twilight, including death, are not truly endings.

Within less than two centuries, the stability won in those early decades of the fourth century would be ripped to shreds: the empire, sinking into decay, would be destroyed, Rome would be sacked, and once again, Christians would be forced to contemplate the shadows of the present age and the hope of Christ’s return. Looking back, it is clear how important it would be for those Christians to keep that hope alive.

In our time, too, the shadows of war and illness and injustice still lurk in the corners, even as creature comforts, technological advances, and prosperity seek to distract us and make us complacent. How are we to remain alert and ready for the coming of Christ?

If we attune our ears, we can hear it in the chant of the earliest Christians, singing psalms as they were led to martyrdom; we can hear it in the hymn of lamp-lighting sung by the Cappadocians during the fourth century; and we can hear it in our own time in Ukrainians singing their prayerful song in the face of imminent calamity. To sing as a Christian isn’t to deny or avoid the fallen realities of the world in some sort of escapism; rather, it is to enter into the midst of them, and to declare that though the darkness may seem strong, a light shines in the darkness which the darkness cannot comprehend (John 1:5), and which, in the fullness of time, will banish the darkness for good. In song, the signs of Christ’s coming continue to shine brightly for those who have eyes to see, ears to hear, and lungs to sing.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

June De Wit

Than you for this transcendent, beautiful write.

Paul Brandenburg

Joel, Thank you. I have long appreciated the power of singing to enhance prayer, especially in the face of suffering and persecution, but your explicit recognition of the tradition of singing psalms, and hymns and prayers as participation in the Parousia is truly profound. Thank you.

bill canonico

"I shall sing to Yahweh all my life, make music for my God as long as I live." Psalm 104:33 i've been singing for nearly all my life and writing songs for over 40 years, about nearly everything; love, loss, family, nature, God, current events, etc. i hope to continue to write and sing for as long as i live here, and forever, after.

stan koki

incredible article. amen!

Joel Webb

Thank you for this call to hope and song that is both deeply scriptural and a sign to those seeking after the light in this present darkness. If the Lorica of St. Patrick is an example, the Celtic saints also pursued this practice. They perceived the purposes of God to fulfill the kingdom in the activity of Creation. Thank you for this powerful reflection and call to prayer without ceasing. May Jesus be praised!

Jerry kendall

Google Pete Seeger’s rendition of How can I keep from singing. Came to mind reading this piece on early Christians singing. Enjoy