Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Covering the Cover: The Violence of Love

-

The Case for Meekness

-

Forum: Letters from Readers

-

Learning Generosity in Syria

-

A Tireless Peacemaker

-

Turning a Corner

-

Behind the Black Umbrellas

-

With Love We Shall Force Our Brothers

-

The Risk of Gentleness

-

The Great Escape

-

Militant Peacemaking

-

Peacemaking Is Political

-

Beyond Pacifism

-

A Life That Answers War

-

Excerpt: Freiheit!

-

Did You Kill Anyone?

-

Poem: “Candid”

-

Poem: “March Thaw”

-

The Minimalist

-

Call to Prayer, Call to Bread

-

Editors’ Picks: “Charis in the World of Wonders”

-

Editors’ Picks: “The Reindeer Chronicles”

-

Editors’ Picks: “I Ain’t Marching Anymore”

-

Editors’ Picks: “Floaters”

-

Poetry You Can Touch

-

Poem: “Annuals”

-

Poem: “The Widow Offers Herself to Life”

-

Poem: “Mary Magdalen Responds to the Harsh Judge”

-

Poem: “In Retrospect”

-

Poem: “A Backward Look”

-

Poem: “Where Nectar Was”

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

On January 21, 1525, a group of fifteen or so friends, mostly young men in their early twenties, gathered at the Zurich house of Anna Manz. What they were there to do was not yet technically illegal, but it soon would be. Georg Blaurock went first: he made his confession of faith, and Conrad Grebel baptized him. The others, one by one, made their confessions; Blaurock baptized them. The first church of the Radical Reformation was formed.

Felix Manz, Anna’s son in his mid-twenties, was one of their number. Two years later and five hundred yards away from her house, he would die, drowned in the Limmat River by order of the city fathers.

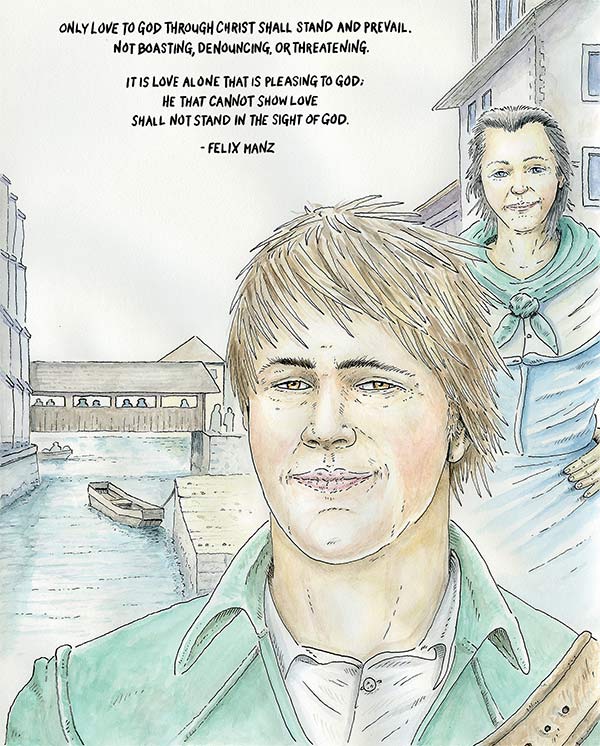

Felix Manz Artwork by Jason Landsel

It had started some years before, in 1519, when a new priest was called to the church in Zurich: Ulrich Zwingli, a scholar and powerful preacher whose exegetical sermons to the people of the city were also passionate calls for them to submit their lives to the Word of God. Felix was drawn to Zwingli’s project: the reform of the Catholic Church – and a translation of the whole Bible into German. The young man, who had a thorough knowledge of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, became Zwingli’s disciple, fellow-worker, and friend.

But he found, as the two men’s work of translation and exegesis went on, that his convictions and Zwingli’s were no longer in harmony. Zwingli’s reforms, he was convinced, did not go far enough: the church, as Felix understood it from the Scriptures, could not be an organization linked to any earthly government; still less could it come under the jurisdiction of the city fathers of Zurich. Moreover, Zwingli called for the baptism of infants to continue as it had when the church of Zurich had been fully following the understanding of Rome. But baptism, Felix was convinced, was a sign of commitment following an adult conversion, a profession of belief, not to be imposed on children who could not yet make such a profession. There was more: Christians, he believed, must not bear the sword nor hold state office; the Christian community must be one in which, at the very least, wealth is shared freely with those in need.

Zwingli continued his controversial preaching. But in 1523, Manz, along with his friend Conrad Grebel, began speaking as well, making their own converts to this more radical way of understanding what Christian commitment meant. Dangerously, several couples with new babies refused to baptize the infants; their consciences would not permit them to do so.

Zwingli called for a public disputation, a debate between himself and his erstwhile fellow translator. On January 17, 1525, the debate took place. The town council declared Zwingli the victor. Manz might not have disagreed: despite his language study, his education was not in the kind of dazzling humanist rhetoric that Zwingli had mastered, nor was his theology as sophisticated. But his conscience, informed by the words he had himself read, could not budge. The council ordered Felix and his group to baptize their unbaptized infants within eight days. Instead, the little group gathered a few days later at Anna’s house – and baptized each other.

For the first Anabaptists in 1525, nonviolence was what separated the church from the world.

Days later, Georg Blaurock, who had come to Zurich to hear the disputation and had been convinced by Felix, interrupted the state church service, standing to speak about the doctrines of the Täufer, the baptizers. The following day, the little circle was raided. Most of the group were arrested and fined. Some paid the fine. Felix, asserting that the city had no jurisdiction over the group of believers, refused, and was for the first time imprisoned.

By spring of that year, Felix was back out and preaching again, somehow having managed a prison break. He was eventually taken up again, but released when he vowed to stop preaching – a vow he promptly broke. The next two years saw the movement grow, despite a new mandate against adult baptism, with violations punishable by death. Finally, on December 3, 1526, Felix and Georg, preaching together, were taken up again.

An illustration from the official account of Felix Manz’s execution; Felix is on the platform, and Anna is somewhere in the crowd.

Georg was sentenced to banishment. Felix, unlike Georg a citizen, was sentenced to death. He did not dispute the charges; he would even then, he said, not refuse anyone baptism, if they were willing to be instructed in the faith. On January 5, 1527, he was led from the prison to a little skiff, preaching to the gathered townspeople as he went. Anna called encouragement to him from the bank of the Limmat. Out in midstream, a pole was run between his bound arms and legs. Those on the bank heard him sing, his voice echoing back toward Anna’s and up to the skies: "In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum." And then he was pressed into the river, held beneath the water until he drowned.

“Only love to God through Christ shall stand and prevail,” he wrote during his last few days in that cell, in a letter to the Täufer, “not boasting, denouncing or threatening. It is love alone that is pleasing to God; he that cannot show love shall not stand in the sight of God. The true love of Christ shall not destroy the enemy; he that would be an heir with Christ is taught that he must be merciful, as the Father in heaven is merciful.

Born out of wedlock, Manz never married, and his travels seem to have taken him no further afield than the outskirts of Zurich. But his conviction that his whole life must be one of obedience to the gospel, as he understood it by his own encounter with the Word of God, led him to become one of the founders of a community that was a radically new way of understanding what Christian commitment means, and then to a death which was the spark of the Radical Reformation.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.