Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Up Hill

-

City of Bones, City of Graces

-

Small Acts of Grace

-

In the Valley of Lemons

-

City of Clubs

-

Save Your Sympathy

-

From “In the Holy Nativity of Our Lord”

-

Digging Deeper: Issue 23

-

Beneath the Tree of Life

-

Sidewalk Ballet

-

The Eternal People

-

Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays”

-

The Pilgrim City

-

Not Just Personal

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 23

-

Madeleine Delbrêl

-

Covering the Cover: In Search of a City

-

Urban Series (Neighborhood)

-

In Search of a City

-

Readers Respond: Issue 23

-

Family and Friends: Issue 23

-

One Inch off the Ground

-

Re-Mapping Belfast

As New York City’s oldest street, the Bowery has long been a magnet for gangsters, hucksters, and hobos. Even today, it is still often the end of the road for homeless war veterans, released felons, people dealing with drug addiction, and others down on their luck.

For one hundred and forty years, Christians of every stripe have come together at The Bowery Mission to offer meals, hot showers, clean beds, and warm clothes. Over the years, the Mission has helped thousands of homeless people get off the streets and back on their feet.

In a new book published by Plough, Jason Storbakken, a Bowery Mission director, retraces that colorful history. Plough asked him to catch up with James Macklin, who first passed through The Bowery Mission’s iconic red doors as a homeless man over three decades ago and is now its director of outreach.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Jason Storbakken: James, can you tell us something about your life?

James Macklin: I was born in Virginia in 1939. My teenage mother put me up for adoption. I was taken into a good home, but my adoptive mother died when I was nine, and I was bumped from one foster home to the next until I found myself on my own at age thirteen.

Since early childhood, I expressed my feelings through song, so I tried to earn a living on the Chitlin Circuit – venues where black entertainers were able to perform during the Jim Crow era. When I couldn’t make ends meet, I joined seasonal workers harvesting cotton and tobacco.

How did you end up on the streets?

I experimented with gambling, alcohol, and marijuana, but it was cocaine that got me hooked, and I began hustling to feed my habit. After years of this lifestyle, I took a job and started saving money, striving to change my ways. I opened my own office-cleaning business, and believed I had conquered my addictions. Temptation surrounded me, however, and this time crack was my downfall. My business toppled, and by 1987 I was adrift on the streets of New York.

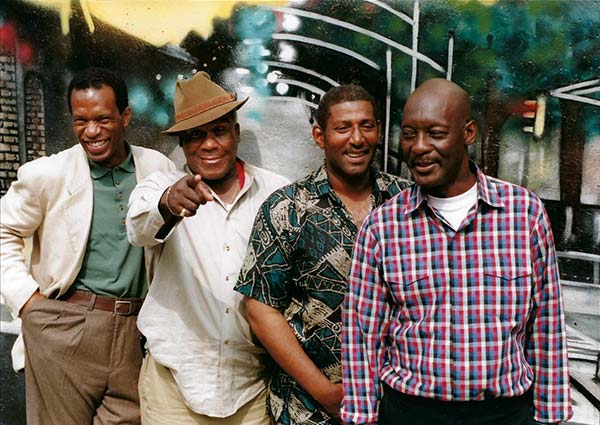

The Bowery Mission’s singing group, Resurrected Beyond Belief (James Macklin pointing)

Photograph courtesy of The Bowery Mission

How did you find your way to The Bowery Mission?

Sleeping on the subway one night, I woke up to hear a woman’s voice saying, “What’s a man like you doing in a place like this?” I opened my eyes to see a white-haired lady holding out a card that offered a meal at The Bowery Mission. Since I was famished, I took the card and followed its directions. And I’ve been there ever since. That was the beginning of a new life. I entered and completed the recovery program and was hired as a Bowery security guard. Three years later, I was promoted to operations manager, and eventually to assistant director.

What’s your role at the Mission now?

Director of Outreach, slash, slash, slash, slash. Whatever comes up. I wear a lot of hats.

From Fanny Crosby to you, there is a long history of music at The Bowery Mission. Tell us a bit about your calling as a musical minister.

Yes, I do a little singing. I’m getting a little older now – I’ll soon be eighty years old – but I still got a note or two left. I used to have a group, Resurrected Beyond Belief, that would travel around the country.

During the 1980s and 90s, the Mission housed a women’s program at 227 Bowery. (It later moved uptown.) These women attended the Mission’s Sunday service, which is how I met Debra, who later joined my musical tours. I would sing, and Debra would share her testimony. In 1995 we were married at The Bowery Mission.

I still do a little singing. I’m going to sing tonight, one song: “Jesus, Keep Me Near the Cross.” That’s my favorite closing hymn.

What have you learned about the life of Christ through your experience at the Mission?

I’ve learned too much to tell you in this interview. But I can tell you being there I’ve learned a lot; I’ve learned more from the men than I think they would ever learn from me. I’m still learning – you stop learning when you’re no longer here. What I know today, you could put it in the thimble the old ladies used to use to sew garments. But I’ve learned how to love people, through finding out it’s impossible to serve people who you don’t love.

Thanksgiving Dinner at The Bowery Mission

Photograph by Frances Roberts/Alamy

How has the Mission changed since you first walked through those red doors over thirty years ago?

Well, when I got there, there was a tremendous discipleship program. Today we have many programs. But discipleship is still the answer. You know, you can call them students, you can call them whatever, but we should all be disciples of Christ, learning to get our lives back together and serve him.

What’s something that has not changed?

I’m beginning to hope and believe that the Mission is built on soup and salvation: feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting the sick. That’s what Jesus would do. You can name them programs what you want to, get all fancy, but changed lives is what matters to me.

How has homelessness changed?

Well, the drugs of choice have changed tremendously. And it’s causing a lot of mental illness. When you are sleeping on the street and from boxcar to boxcar to trolley car to trolley car, you know, you lose your sanity. God didn’t create us to live in the street. So that causes a lot of it. Anyway, we have a lot of mental illness that we have to deal with today. It comes in all forms. And then on top of all that there are the addictions that we suffer.

Recently a young man experiencing homelessness murdered four others as they slept down on the Bowery and in Chinatown. We had a memorial service at the Mission. A lot of people are grieving and trying to figure out homelessness. Is there some kind of meaning or message we can find from this tragedy?

Nobody wants to talk about that book called Revelation, but in the eighteenth chapter of that book all of that is described. It’s really the end time. It’s a shame that a man can’t go to sleep, with nowhere to go in the richest city in the world, and has to be murdered without even knowing what happened. We ought to take a look at ourselves. I think it’s a rude awakening in our neighborhood; I think everybody’s concerned. But it shows you that The Bowery Mission still cares about people, not only in their life but even in their death.

A homeless Vietnam veteran, Larry Mason found a new life through The Bowery Mission.

Photograph from the Bruderhof Archive

You’ve maintained a long friendship and collaboration with the Bruderhof communities.

Yes, we’ve worked together closely for thirty years. Several men who found a new life at The Bowery Mission went on to serve in the Bruderhof. One was Rubén Ayala – he and I graduated from the Bowery program together. He went to the Bruderhof and I stayed here. Larry Mason was another; he was the operations manager at the time. I couldn’t stand the guy at first, but we learned to get along. Larry used to walk around with khaki pants on like he was still in Vietnam, and he ran the Mission with a military attitude. He had a long pony tail that hung down his back. It was Larry Mason and Rex Duval who started the big Thanksgiving celebration for the homeless at The Bowery Mission, back in 1986.

Another of your hats is a ministry with the Amish and Mennonite communities. How did that come about?

There was a gentleman at the Mission by the name of Willie Lawson when I got there, a white gentleman from Tennessee, who could have become a professional baseball player but he was out quail hunting and he had some of his fingers shot off, so that ended that. He introduced me to the Mennonites long ago. When I first met them, their first question to me was had I ever been married. I passed that test and ever since that day, I have been a member of the family. It was more recently I became a friend of the Amish. I had been told that if I got to know them I’d always be blessed, because they’ll always be in your corner. And I’ve found that to be true. I’ve been blessed beyond compare.

Where does all the food come from to feed almost a thousand people a day?

Well, at one time nigh on 60 percent came from Lancaster, Pennsylvania. I guess it’s still up around that figure. But we’ve improved upon the giving situation, with Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s and a host of restaurants around the city. I think if you look at the figures you’d wonder how we do it – three meals a day, free to anybody who comes through the red doors. I’ve been there thirty-three years and I have never ever seen a time when we couldn’t feed our people – not a single day.

What’s your favorite meal when you’re down at the Bowery?

Well, I’ll tell you the truth, I’m sorta strict with my diet. I’m a picky eater. But there are times when I can go down there and find myself a good old piece of fried chicken. And I can always eat because Whole Foods gives us stuff that has shelf life and I can eat the fruits and veggies. I don’t eat the lobster – we get those kinds of things but I don’t eat them. The Mission is not just a soup kitchen; we have a variety of food. Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s have really changed the way we diet at the Mission.

Thanksgiving dinner servers

Photograph courtesy of The Bowery Mission

What’s the motto of the kitchen?

“Serve like you’re serving a king.” That’s the same thing I spoke about earlier: feed the hungry, clothe the naked, visit the prisoners – transform lives. The nearest way to a man’s heart is in the kitchen. That’s how our wives keep us – they learn to feed us. When you can do that you keep a happy person.

If there were one thing you wished everyone would know about those experiencing homelessness, what would that be?

Fanny Crosby, when she used to speak in the chapel, would say to the men: “You don’t have to tell a man he’s a sinner – he knows that already.” So what we gotta try to do is live out the example of Christ as we walk from day to day. Live out that example. It’s hard to do sometimes, but we’ve got to learn to do it if we want to make it into the kingdom.

Any final thoughts?

Remember this: Never look down on a human being, whether it’s a man, woman, or child, unless you’re trying to pick them up. And all the days of your life you will be blessed.

The Bowery Mission honored James Macklin at its 18th Annual Valentine Gala on February 14, 2017. Macklin entered the Mission's red doors for help from addiction 30 years ago and has had a life transforming impact in the lives of thousands of homeless and hungry New Yorkers.

James Macklin is the director of outreach for The Bowery Mission.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Debra

Thank you for your testimony of faith and love.